|

By

Thomas J.

Aveni, MSFP

The Police Policy

Studies Council

December 2006

On the weekend of November 25-26th, after a dramatic NYPD shooting

incident, local and national media sources screamed inflammatory

headlines, such as; “Fiancée of Slain Groom Calls Police 'Murderers'”[i]

and “Unarmed Groom Killed By NYPD Bullets.”[ii]

And, so we were told of how seven NYPD officers,

members of an undercover team that was investigating drug and

prostitution activity at a seedy bar, committed an unspeakable atrocity

against three young men who were (by omission of salient background

information) characterized as innocent victims of “trigger-happy”

police. But, in your heart-of-hearts, you know the other side of the

story wasn’t being told. On the weekend of November 25-26th, after a dramatic NYPD shooting

incident, local and national media sources screamed inflammatory

headlines, such as; “Fiancée of Slain Groom Calls Police 'Murderers'”[i]

and “Unarmed Groom Killed By NYPD Bullets.”[ii]

And, so we were told of how seven NYPD officers,

members of an undercover team that was investigating drug and

prostitution activity at a seedy bar, committed an unspeakable atrocity

against three young men who were (by omission of salient background

information) characterized as innocent victims of “trigger-happy”

police. But, in your heart-of-hearts, you know the other side of the

story wasn’t being told.

Certainly,

provocative actions by the three “unarmed” suspects initiated the tragic

series of events that transpired that morning. People who frequent

disreputable night clubs, have extensive criminal records, solicit

prostitutes, announce (within earshot of police), “Yo, get my gun!” and

then use their vehicle as a battering ram against undercover police

vehicles, are seldom innocent victims of the dangerous circumstances

that they’ve created. But this article isn’t about placing blame for

what transpired that day. It’s about setting the record straight about

officer-involved shootings that involve numerous officers in incidents

that have been erroneously termed “contagious fire” episodes.

What do we know

about incidents in which multiple officers are involved in a gunfight?

Unfortunately, what we know is dwarfed by what we don’t know. And that

is precisely the reason why so many “experts,” with few facts, have been

allowed to offer what are at times outlandish hypotheses about why these

incidents often result in tragic consequences. Even the terminology

bandied about is problematic, and contributes to even greater

misunderstanding. Having admitted this, it would be best to begin

establishing acceptable terminology with which to begin examining at

this phenomenon in more detail.

“Bunch Shootings”

The

genesis of the term “bunch shooting,” as it applies to multiple officer

shootings, is unclear. The first time that the author can remember

seeing this term used was in a 1992 article

[iii]

that appeared in the Oregonian newspaper – an

article that made some oblique references to the fact that officers that

fired in “bunches” tended to fire a higher ratio of rounds per officer,

per incident. Since the article loosely examined incidents involving an

agency that had been transitioning from revolvers to pistols, and which

had suspended handgun training for nearly two years due to manpower

constraints, it was difficult to discern whether the Portland Police

statistics offered a reliable insight into the “bunch shooting”

phenomenon.

The Contagious Misnomer

When looking for the

wellspring of the term “contagious fire,” we are drawn to the field of

clinical psychology. There we find the likely genesis of the term in the

phrase “emotional contagion.” An ‘emotional contagion' is the tendency

to feel emotions that are similar to and influenced by those of others.

This sounds innocuous enough, right? Not really. This is often cited as

being analogous to yelling “fire” in a crowded theater, instigating a

stampede of undisciplined, panic-stricken people. Does this analogy best

represent the behavior of police when involved in a bunch shooting?

There is a paucity of evidence to support any such conclusion.

“Synchronous Fire"

The term,

“synchronous fire,” is gaining acceptance as a label for

multiple-officer shootings, and it deserves closer examination. The

generic definition of synchronous action is that which occurs or exists

at the same time, moving or operating at the same rate. In the real

world, synchronous fire generally isn’t what that generic definition

would imply. A bystander may hear what he thinks is a steady stream of

gunfire, but upon closer examination, we’ll find that some officers

fired while others did not, or that some fired their magazines empty

while others did not. However, there is another dimension to

synchronicity, and it’s one that may be worth embracing.

Swiss

Psychologist, Carl Jung, postulated

[iv]

that “synchronicity” was best described as,

"temporally coincident occurrences of acausal

events." Jung spoke of synchronicity as an "acausal connecting

principle" (i.e. a pattern of connection that cannot be explained by

direct causality). In Jung's mind, cause-and-effect seemed to have

nothing to do with it. Jung explained that synchronicity, while not a

matter of coincidence,

is the experience of two or more occurrences

that are logically meaningful (but inexplicable) to the persons

experiencing them.

Jung’s definition of a

synchronous event could logically explain the phenomenon of parallel

events or circumstances that we see in multiple-officer shootings;

interconnected in space and time, yet not cleanly connected in

causality.

“Mass Reflexive Response”

In 1999, four NYPD

“street crimes” unit officers found themselves involved in the tragic

mistake-of-fact (low light) shooting of Amadou Diallo. After mistaking

an object in Diallo’s hand for a gun, the four officers fired a total of

41 shots at Diallo, striking him 19 times. Thereafter, a new phrase

began creeping into the NYPD lexicon; “mass reflexive response.” The

definition that we’re given for “mass reflexive response” is;

"Gunfire that spreads among

officers who believe that they, or their colleagues, are facing a

threat. It spreads like germs, like laughter, or fear."

When examining

this definition, few would challenge the central part of this definition

regarding officer perception of events; “….who believe that they, or

their colleagues are facing a threat..” But, when bracketed between the

rest of the verbiage (“Gunfire that spreads…..like germs, like laughter,

or fear”) this definition becomes extremely problematic.

Additionally this

definition is also interchangeable enough to be used verbatim to define

“contagious fire,” and it often is. Before you allow this terminology to

seduce you, let’s examine the core issues that are routinely overlooked

by “experts” and the media.

Lowlight, Multiple-Officer

Confrontations

We all

recognize the fact that threat identification is extremely problematic

under low light conditions. So much so that up to 75%[v]

of all police “mistake-of-fact shootings” occur under low light

conditions. So what does this have to do with police bunch shootings?

The correlation between low light conditions and bunch shootings that

end in mistake-of-fact tragedies is quite compelling.

Daylight shootings, and even diminished light

shootings where facts are clearly established, tend to have far fewer

unarmed suspects shot mistakenly. And, when

confronting the question about whether we are more concerned about

whether the decision to shoot was appropriate or whether the number of

rounds fired was “excessive,” it’s quite clear that the root of

community outrage originates in why we shoot more than how many rounds

that we fire thereafter. A high volume of fire may throw gasoline on the

fire, but community outrage is almost always initiated by the perceived

lack of justification for using deadly force.

Case

studies of bunch shootings that have occurred under low light conditions

aren’t as ubiquitous as we’d like, but what we do have at our disposal

exhibits many common tendencies. There are many cases to cite, but two

compelling examples come immediately to mind.

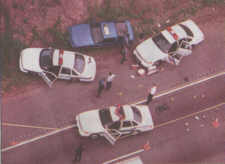

June 3, 1999, on

Interstate 80 in Parsippany-Troy Hills, New Jersey, Stanton Crew, was

shot and killed by four police officers from several jurisdictions.

Police had boxed in his car with their vehicles and he allegedly tried

to escape by maneuvering around them. His driver’s license was suspended

for lapsed insurance, and as he drove home, a cop tried to pull him over

for “driving erratically.” Reportedly afraid that he would not be able

to afford the fines for driving an uninsured car, Mr. Crew allegedly

sped up, going 70-80 mph for ten miles. He then crossed the median and

drove five miles in the other direction before being boxed in. Police

claim they feared that Mr. Crew was going to run them over. Cops fired

27 shots at his car, killing Mr. Crew and wounding his passenger. Though

reports stated that police feared Crew’s vehicle presented a threat to

their safety, after-action analysis suggested that the police units that

boxed-in Crew’s vehicle found themselves in a crossfire of their own

making (see photo), with police rounds striking other police vehicles.

This likely added to the confusion present as to the degree of threat

that Stanton Crew presented. Analysis: Vehicular pursuit, low light conditions,

suspect behavior that was perceived to be assaultive, and possible

confusion about the origin of gunfire striking police units, and we have

four officers firing 27 rounds at an “unarmed” individual. June 3, 1999, on

Interstate 80 in Parsippany-Troy Hills, New Jersey, Stanton Crew, was

shot and killed by four police officers from several jurisdictions.

Police had boxed in his car with their vehicles and he allegedly tried

to escape by maneuvering around them. His driver’s license was suspended

for lapsed insurance, and as he drove home, a cop tried to pull him over

for “driving erratically.” Reportedly afraid that he would not be able

to afford the fines for driving an uninsured car, Mr. Crew allegedly

sped up, going 70-80 mph for ten miles. He then crossed the median and

drove five miles in the other direction before being boxed in. Police

claim they feared that Mr. Crew was going to run them over. Cops fired

27 shots at his car, killing Mr. Crew and wounding his passenger. Though

reports stated that police feared Crew’s vehicle presented a threat to

their safety, after-action analysis suggested that the police units that

boxed-in Crew’s vehicle found themselves in a crossfire of their own

making (see photo), with police rounds striking other police vehicles.

This likely added to the confusion present as to the degree of threat

that Stanton Crew presented. Analysis: Vehicular pursuit, low light conditions,

suspect behavior that was perceived to be assaultive, and possible

confusion about the origin of gunfire striking police units, and we have

four officers firing 27 rounds at an “unarmed” individual.

February 20, 1998, on Route

195 in Swansea, Massachusetts, at about midnight, an incident occurred

in which four officers from two adjoining jurisdictions engaged Richard

Parker in a brief vehicular pursuit for what was initially a motor

vehicle violation. As Parker lost control of his vehicle at exit 185,

he exited his vehicle and had four officers engage him with a total of

50 rounds fired. Six of those 50 rounds strike Parker, but he survives

the incident. Officers, hampered by adverse light conditions where the

chase culminated, stated that they saw Parker’s hands come together as

he exited the vehicle. They also stated that they saw something

reflective in his hands. Post-incident analysis indicated that Parker’s

shiny leather gloves likely misled officers into believing that he had a

handgun, as did his physical posture as he exited his vehicle.

Analysis: Low light conditions,

along with compelling situational and behavioral cues exhibited by the

suspect, resulted in 50 rounds being fired by four officers at an

“unarmed” suspect in a few brief seconds.

Pandemonium, Not “Panic”

Events of May 9,

2005 in Compton, California, were brought into the living rooms of

millions of Americans. Captured on video was the aftermath of a 12

minute vehicular chase in which 13 deputies from the Los Angeles County

Sheriff’s Department engaged an “unarmed” suspect with over 120 rounds

of handgun fire. The suspect, 44-year-old Winston Hayes, was hit only

four times and survived. Yet another example of a low light

multiple-officer shooting, there was apparent confusion (before any

rounds were fired) after one deputy fell near the suspect’s moving

vehicle. Again we have a low light shooting that likely sprung from

confusion and mistake of facts. However, as you watched the deputies

fire, with many standing upright without utilization of cover, panic was

not outwardly apparent. Was there a “mass reflex” of 13 deputies to fire

simultaneous volleys? Or, in the confusion of the night, did 13 deputies

make 13 individual errors in judgment? Can one officer’s error influence

the decision-making of other officers? Absolutely, it happens all of the

time. But, this is a far cry from being anything we might liken to an

“emotional contagion.” Events of May 9,

2005 in Compton, California, were brought into the living rooms of

millions of Americans. Captured on video was the aftermath of a 12

minute vehicular chase in which 13 deputies from the Los Angeles County

Sheriff’s Department engaged an “unarmed” suspect with over 120 rounds

of handgun fire. The suspect, 44-year-old Winston Hayes, was hit only

four times and survived. Yet another example of a low light

multiple-officer shooting, there was apparent confusion (before any

rounds were fired) after one deputy fell near the suspect’s moving

vehicle. Again we have a low light shooting that likely sprung from

confusion and mistake of facts. However, as you watched the deputies

fire, with many standing upright without utilization of cover, panic was

not outwardly apparent. Was there a “mass reflex” of 13 deputies to fire

simultaneous volleys? Or, in the confusion of the night, did 13 deputies

make 13 individual errors in judgment? Can one officer’s error influence

the decision-making of other officers? Absolutely, it happens all of the

time. But, this is a far cry from being anything we might liken to an

“emotional contagion.”

Influence of Adversary’s Weapon

Does the capability of an

adversary’s weapon have a discernable influence on the volume and

efficacy of police gunfire? Absolutely. Observational research of Los

Angeles County shootings (1998-2002) suggested that bunch shootings were

three times more likely to involve suspects armed with shoulder weapons

(i.e., rifles and shotguns). How critical is that as an incident

variable? (see comparison table below) Anyone watching dramatic video of

the 1997 “North Hollywood Shoot-Out” noticed how much distance officers

maintained from the two heavily armed and armored suspects (Phillips and

Matasareanu) who fired more than 1,100 rounds at many of the more than

350 officers who responded to that call. The suspects were armed with an

assortment of fully automatic and semi-automatic weapons that included

AK-47 variant rifles, an H&K 91 (.308) and AR15 (.223). Of the hundreds

of pistol and shotgun rounds fired by police, the suspects sustained a

total of only 40 hits[vi]

(Phillips was shot 11 times and Matasareanu was shot 29 times). The body

armor worn by the suspects defeated many of the 9mm and buckshot rounds

fired at them by police. Greater standoff distances (between police and

adversaries) diminish police hit ratios, which in turn tends to invite a

greater volume of police fire. Does the capability of an

adversary’s weapon have a discernable influence on the volume and

efficacy of police gunfire? Absolutely. Observational research of Los

Angeles County shootings (1998-2002) suggested that bunch shootings were

three times more likely to involve suspects armed with shoulder weapons

(i.e., rifles and shotguns). How critical is that as an incident

variable? (see comparison table below) Anyone watching dramatic video of

the 1997 “North Hollywood Shoot-Out” noticed how much distance officers

maintained from the two heavily armed and armored suspects (Phillips and

Matasareanu) who fired more than 1,100 rounds at many of the more than

350 officers who responded to that call. The suspects were armed with an

assortment of fully automatic and semi-automatic weapons that included

AK-47 variant rifles, an H&K 91 (.308) and AR15 (.223). Of the hundreds

of pistol and shotgun rounds fired by police, the suspects sustained a

total of only 40 hits[vi]

(Phillips was shot 11 times and Matasareanu was shot 29 times). The body

armor worn by the suspects defeated many of the 9mm and buckshot rounds

fired at them by police. Greater standoff distances (between police and

adversaries) diminish police hit ratios, which in turn tends to invite a

greater volume of police fire.

Much was learned

from the North Hollywood shootout about police preparedness for similar

situations. But, overlooked was the fact that many officers were able to

respond with discipline through their own fears. Emotional contagion?

Where? Outwardly, it appears as if each officer experienced his/her own

version of hell, more than likely oblivious to everyone else’s personal

vision of hell. Mass reflexive response? Generally speaking, officers

hunkered down behind cars and concrete walls and fired only when an

opportunity presented itself.

|

AGGREGATE

SYNOPSIS

LOS ANGELES

COUNTY OFFICER-INVOLVED SHOOTINGS† 1998-2002* |

|

Shots Fired Per Officer With Only 1 Officer

Involved |

3.59 |

|

Shots Fired Per Officer With 2 Officers

Involved |

4.98 |

|

Shots Fired Per Officer With More Than 2

Officers Involved |

6.48 |

|

Hit Ratio In OIS With 1 Only Officer Involved

|

51% |

|

Hit Ratio In OIS With 2 Officers Involved

|

23% |

|

Hit Ratio In OIS With More Than 2 Officers

Involved |

9% |

|

* At the time this was originally published,

shooting data for 2002 was only available to September 23rd.

†

Data provided did NOT include data for

incidents where shots fired by officers had no suspect being

struck by fire.

|

Toward A More Global

Perspective

Much of the

emotional hysteria that we see exacerbated by the media tends to focus

on the fact that officers are now issued high-capacity handguns that

“encourage” high volumes of police fire. This transition has nudged the

number of shots fired per officer, per incident upward, but it has

absolutely no bearing on our decision to employ deadly force. In 1973,

when NYPD officers were all issued six-shot .38 Special revolvers, there

were 1.82 fatal police shootings per 1,000 officers; in 2005, there were

0.25 such shootings per 1,000 officers, bringing the absolute number of

police shootings down from 54 in 1973 to nine in 2005[vii].

The NYPD’s per capita rate of shootings is lower than many big city

departments.

With more than

37,000 uniformed officers, the NYPD is by far the country's largest

police force. Its police shootings often become fodder for the national

news outlets, yet NYPD seldom gets a fair shake in the media. At the

time this article was authored, December 9, 2006, NYPD has killed a

total of 11 suspects. To put NYPD shooting restraint in better

perspective, consider that so far this year, at least 19 people have

been killed by police in Philadelphia. Las Vegas, which has about 2,170

police officers, has had 12 people shot and killed by police so far this

year. In suburban Atlanta's DeKalb County, police have fatally shot 12

people so far this year. DeKalb County, with 700,000 residents, is

one-tenth the size of the New York City.

Clearly, so much

is lost in the emotion and noise generated by special interest groups in

the aftermath of a police shooting. If truth is truly the first victim

of war, perhaps the same can be said for the media “mugging” of truth in

the aftermath of a police shooting.

When examining multiple-officer shootings, we tend to see several

recurring variables that have profound training and policy implications.

However, we see so many dissimilarities in specific officer behaviors

that we should avoid succumbing to sweeping generalities. Characterizing

officer shooting behaviors as being “contagious” or “reflexive” should

be avoided until specific facts and circumstances have been exhaustively

evaluated.

[i]

http://www.cnn.com/2006/US/11/27/nyc.shooting.ap/index.html

[ii] http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2006/11/26/national/main2208778.shtml

[iii] The Oregonian,

April 25, 1992, “Shootings: Who, What and How Many”

[iv] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Synchronicity

[v] Aveni, Thomas.

“Following Standard Procedure.” Law & Order, Vol. 51, No. 8,

August 2003

[vi] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/North_Hollywood_shootout

[vii] http://www.city-journal.org/html/eon2006-12-04hm.html

|