OFF BALANCE:

|

|

There are obviously more crimes committed in America each year than the news media have time or space to cover. As such, as in all other fields of endeavor, reporters, editors, and producers must make choices. The following summary digested with permission from Kids and Guns: How Politicians, Experts, and the Media Fabricate Fear of Youth (Common Courage Press 2000) by Mike Males, Ph.D., discusses which homicides were chosen for national coverage when school shootings were grabbing headlines in the late 1990's. In a 30-month period from May 1977 to November 1999, in Ventura, California, three affluent suburban adults in their 40's killed 10 people in multiple-victim rage shootings -- six children and four adults. That's more than the combined toll of headlined shootings by high schoolers in Pearl, Mississippi; West Paducah, Kentucky; and Jonesboro, Arkansas -- all in just one county. Yet none of the Ventura grownup shootings (44-year-old man guns down screaming wife and three children; 43-year-old man rakes two neighbors with bullets as three-year-old shrieks in terror; 42-year-old mom blasts three boys in their beds in ritzy rural home) made national headlines. All the usual big story ingredients were there: well-off perpetrators coldly mowing down innocent children in communities where "murder just does not happen" with carnage so bloody law enforcement veterans required counseling. The only big-story ingredient missing: the murderers were not youths. Consider the dozen mass shootings in the last half of 1999. All involved adult perpetrators in their 30's and 40's, of middle-class or wealthier status, 11 of them men. The toll was 90 casualties: 59 dead (including 21 minors) and 31 wounded. Thus, just 25 weeks of middle-aged mass shootings killed and injured far more people than three years of highly publicized school shootings (Columbine 16; Jonesboro four; West Paducah three; Springfield two; Pearl two; Mt Morris Township one). All occurred where "such things are not supposed to happen": professional offices, churches, Bible study groups, community centers, upscale hotels, suburban homes, or in posh enclaves. A few received press attention (the Atlanta office mass-murder received cover-story treatment) but the media quickly wearied of the sheer number of middle-aged killings. Likewise, the news media made choices about coverage even within the category of school shootings. According to the National School Safety Center, over the 1997-99 school years there were 30 school killings which received practically no publicity resulting from 26 incidents involving 28 killers in cities from Hoboken, New Jersey, to Pomona, California. The deaths fell into two categories. Twenty-two involved student victims who were Black, Hispanic, Asian, or of unknown race (the six whose races were not reported attended mostly-minority schools). Eight involved white victims -- of those five were adults killed by adults, two were students killed by adults, and one student died from a previously undiscovered aneurysm after a fist fight. In the super-charged 1999 school year when the media feverishly awaited any new school shooting, three were completely ignored. A 14-year-old Elgin, Illinois, teen was shot to death in his classroom in February. Not news: he was Latino and in Special Ed. On June 8, two girls were gunned down in front of their high school in Lynwood, California, south of Los Angeles. Not news (even in the Los Angeles Times which ran a modest 440-word story on an inside page): they were Latinas. On November 19, a 13-year-old boy shot a 13-year-old girl to death in a Deming, New Mexico, middle school. Both were also Latinos. Several of the unheralded school killings had death tolls equaling or exceeding nationally headlined killings. Why then did the news media deem white-suburban-student killings an apocalypse and white adult minority student and inner-city killings of no import? To ask the question is to answer it: in the crass logic of the newsroom things like that are "supposed to happen" to darker-skinned youth. |

Perpetrators. The coverage of perpetrators of color is less out of balance than the coverage of victims. Some studies found distinct disparities, while others found perpetrators of color represented in numbers that matched their local arrest rates, but found Whites underrepresented. For example, a study of murder coverage in Indianapolis newspapers found that the percentage of articles about Black suspects reflected the percentage of Blacks arrested for murder (60% and 61%, respectively), but if the suspect was Black, the average article length was longer than for a White suspect.66

RMMW’s study of local TV news across the country in 1995 found that 37% of perpetrators on local TV news were Black, 32% were Latino, 27% were White, and 4% were Asian. Whites dominated most other roles on local TV news in the nation that day, comprising 89% of the anchors, 78% of the reporters, 87% of the official sources, and 80% of the victims.67 Nine months later the numbers were nearly identical.68

Close looks at local TV news in a major media market and large urban center found disparities as well. Blacks were 22% more likely to be shown on local TV news in Los Angeles committing violent crime than nonviolent crime, while according to police statistics, Blacks were equally likely to be arrested for violent crime and nonviolent crime. Likewise, Hispanics were 14% more likely to be depicted as committing violent crime than a nonviolent crime, whereas Hispanics were 7% more likely to be arrested for a violent crime than a nonviolent crime.69 Some might argue that this is simply because violent crime is more newsworthy than non-violent crime. But Whites were 31% more likely to be depicted committing a nonviolent crime than a violent crime, whereas Whites were in fact only 7% more likely to be arrested for a nonviolent crime than a violent crime. Thus, while Blacks and Hispanics were overrepresented as violent offenders, Whites were underrepresented as violent offenders on the evening news. In addition, researchers found that when stories featured a Black perpetrator, reporters included sources hostile to the perpetrator half the time, whereas with White perpetrators, reporters included hostile sources only 25% of the time.70

How are African Americans depicted in crime stories? In his extensive work on portrayals of African Americans on local television news71 , Professor Robert Entman documents that Blacks are most likely to be seen in television news stories in the role of criminal, victim, or demanding politician. Black suspects were less likely to be identified by name as were White suspects; were not as well dressed as White suspects on the news; and were more likely to be shown physically restrained than Whites. In sum, Black suspects were routinely depicted as being poor, dangerous, and indistinct from other non-criminal Blacks. He also found that Blacks are more frequently reported in connection with violence, and that Black suspects and their defenders were substantially less likely to speak in the stories than were their White counterparts, reinforcing their absence of individuation.72

Are Blacks blamed for crime? Romer et al. (1998) wanted to find out whether the overrepresentation of people of color, especially African Americans, in stories about crime and other problems was simply an accurate reflection of the crime that Blacks committed or the consequence of journalists’ interpreting Black crime as intergroup conflict. They posited that if Blacks are shown accused of crimes, but not affected by crime or active in prevention efforts, the blame interpretation would persist in viewers. The authors examined more than 3,000 stories from 14 weeks of local TV news in Philadelphia. They found Blacks overrepresented in crime stories and more likely to be shown as perpetrators in violent and nonviolent crime (though one station had a more balanced portrayal, with higher rates of Blacks in nonviolent roles). They found Whites represented as victims at a greater rate than as perpetrators, ranging from 30-70%73 , all of which were greater than Whites’ rate of victimization according to police statistics in Philadelphia. Despite much higher rates of Black victimization according to the FBI, White victims are shown at a much higher rate on the news. They found that "persons of color are represented in the crime category primarily for their contribution to crime," whereas Whites "are shown primarily for their reaction to and suffering from crime."74 Romer et al. conclude that these depictions overemphasize the harm people of color inflict on White victims, perpetuate tension between groups, and inhibit cooperation.

Interracial Crime. Our nation has an ugly history of treatment of interracial crime, dating from slavery through the "Jim Crow" era to the well-documented fact that today Blacks have a higher risk of receiving the death penalty for killing Whites than any other victim-offender racial mix.75 That history is reflected in public opinion polling on race and crime that shows that Whites overestimate their likelihood of being victimized by minorities by three to one.76 The research we examined found that depictions of interracial crime were emphasized. On local TV news in Philadelphia, four in ten stories about non-White perpetrators depicted a White person as a crime victim, whereas only one in ten homicides with a minority perpetrator actually involved a White victim.77 Likewise, interethnic homicides were 25% more likely to be reported in the Los Angeles Times than their actual occurrence in Los Angeles in 1990-1994.78 On local television news in Chicago, 76% of Chicago news about Blacks was crime or politics, with stories about Black victimizations of Whites being especially prominent.79 These findings are disturbing since people of any racial group are far more likely to be killed by someone of the same race.

Contradictory Evidence. The evidence of distorted news portrayals of race and crime is strong, but there are some exceptions. A content analysis of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch did not find African American portrayals limited to stereotyped roles of perpetrator or entertainer.80 The authors suggest that this may be the result of a heightened awareness by the newspaper staff to combat such stereotypes. Another study found that homicides allegedly committed by Blacks or Hispanics tended to be covered less extensively than homicides allegedly committed by Whites.81 Another found no significant difference in the depictions of African Americans and Whites in the [Orlando] Sentinal Star in news coverage during 1980, though crimes considered newsworthy most often involved African Americans, and so it was those crimes that were more likely to appear in the paper.82 A reporter told those researchers that racial identification in a crime story "was something I was told to leave out".83 Finally, researchers conducted a "baseline" content analysis of 1980 newspapers to determine the prominence of coverage of Mexican Americans, their representation, characterization, and whether there is any variability in those depictions.84 Though Mexican Americans are generally underrepresented in American newspapers, the researchers did not find an overemphasis on crime reporting.85 However, more recent research indicates that Latinos rarely appear in the news, and when they do it is likely to be in stories about crime or immigration.86

Summary and Implications. Despite some evidence to the contrary, 75% of studies that investigated the race of perpetrators conclude that people of color are disproportionately associated with violent crime as suspects in news stories. Six out of seven studies that examined the race of victims found a consistent under-reporting of people of color as victims of crime. In news coverage, Blacks are most often the perpetrators of violence against Whites and other Blacks, whereas in reality Whites are six times as likely to be homicide victims at the hands of other Whites.87 Other summaries of content analyses have found that African Americans and Latinos are more often portrayed as criminals and less frequently shown as victims.88 Consequently, it appears that most Americans are given an erroneous picture of racial violence and who suffers most often from crime, as attested to by public opinion surveys. In particular, the absence of Black victims, coupled with the repeated presence of Black suspects across different sources of news, reinforces stereotypes about African Americans as a group audiences should fear.

Finding #4: Few studies examine portrayals of youth on the news. Those that do find that youth rarely appear in the news, and when they do, it is connected to violence.

There is substantially less research that focuses on portrayals of youth in the news.89 Though the findings are consistent, there are fewer of them. Of the 146 articles we originally identified, only 16 examined whether and how youth were portrayed on television news or newspapers.90 Despite the small number of studies, the findings are consistent with the emphasis on violent crime in news coverage generally. Thus, when youth appear in the news, it is often connected to violence. There is also evidence that youth appear in violent contexts, as we might expect since most crime news is violence-related. A few of the studies also parallel the general findings on race and the news. Young people of color seem to fare as poorly as adults on the news – perhaps worse. Finally, some studies find that violence perpetrated by adults upon youth is underreported.

News Involving Youth is Violent. Stories about youth in newspapers and on television news are scarce. When they do appear in the news, youth usually are in stories about education or violence.91 Relatively few youth are arrested each year for violent crimes, yet the message from the news is that this is a common occurrence. The earliest study we found to focus on youth and crime in the news was an examination of Minnesota newspapers published between July 1, 1975, and June 30, 1976.92 Overall the study found that images of boys emphasized theft and violence primarily because status offenses were not included in coverage. By failing to report on status offenses, which represent the more common problems facing a greater number of young people, the news picture of youth, like adults, is focused on the more unusual yet far less frequent crimes. As with crime coverage generally, theft and violence committed by youth are more serious than status offenses. Still, the authors were concerned that the absence of the lesser offenses in the picture means that delinquents "are presented as inevitably bad, and, if left untreated, they will inevitably go wrong."93

Studies of how juvenile crime was covered over 10 years in Hawaii’s major dailies, The Honolulu Star Bulletin and The Honolulu Advertiser, showed extreme distortions of juvenile crime.94 From 1987 to 1996, the newspapers’ coverage of juvenile delinquency increased 30-fold. The newspapers’ coverage of gangs increased 40-fold; the most frequent type of juvenile crime story reported by the newspapers was "gang activity." This exploding coverage did not simply reflect higher rates of crime and violence among Hawaii’s youth. On the contrary, unlike the rest of the country, Hawaii saw its juvenile crime rates decline or remain stable during the same period. The authors conclude that since most Hawaii residents "believe the media do a fairly good job reporting crime news" and news media are the primary source for that news, it appears that many people perceive the nature of juvenile crime in Hawaii to be typified by violent and/or gang-related offenses.95 In fact, in Hawaii most youth are arrested for less serious offenses such as vandalism, running away from home, drug possession and fighting.96

An analysis examining 840 newspaper stories and 109 network news segments in 1993 showed that 40% of all newspaper stories on children were about violence, as were 48% of network television news stories.97 Nominal attention was given to topics of family, health, or economic concerns. There was more overall coverage of crime and violence than of all other policy issues combined. In a later study that examined 3,172 randomly selected stories on youth in one year of the Los Angeles Times, Sacramento Bee, and San Francisco Chronicle, researchers found that the newspapers focused largely on two topics: education and violence. No other topic rated even a third as much attention. Education stories comprised 26% of all stories involving youth. The authors maintain that this is appropriate since the vast majority of youth between the ages of 5 and 17 attend school and about half continue after high school. But violence stories made up 25% of all youth coverage, when only three young people in 100 perpetrate or become victims of violence.98

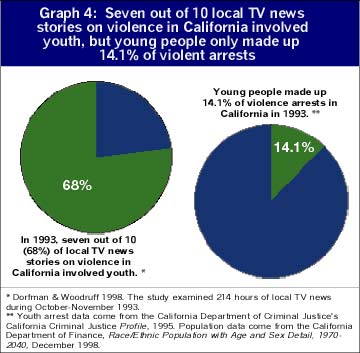

The circumstances in which youth are seen on television news are similar. A study of youth on local television news in 1993 examined 214 hours of local television news broadcast over 11 days on 26 stations throughout California.99 More than two-thirds of violence stories involved youth while more than half of all stories that included youth involved violence.100 One out of every two (53%) TV news stories concerning children or youth involved violence, while California crime data show that one out of every 50 (2%) young people in California were either victims or perpetrators of violence in 1993. (See Graph 3.) Nearly seven in 10 news stories (68%) on violence in California involved youth, whereas youth made up 14.1% of violence arrests in California that year.101 (See Graph 4).

Young people had to perform extraordinary feats to appear on local television

news in non-violence-related circumstances. For example, in the fall of 1993, a

story ran on local stations across the state on the youngest person to fly solo

across the country. Stories about youth accomplishments accounted for 1.2% of

the total news time in the study, and these stories rarely featured local young

people – most were stories provided to local stations intact via their satellite

feed services.

Young people had to perform extraordinary feats to appear on local television

news in non-violence-related circumstances. For example, in the fall of 1993, a

story ran on local stations across the state on the youngest person to fly solo

across the country. Stories about youth accomplishments accounted for 1.2% of

the total news time in the study, and these stories rarely featured local young

people – most were stories provided to local stations intact via their satellite

feed services.

In a more recent study of youth depictions on network and local TV news, researchers found a similar paucity of stories on youth active in community life or achieving success. On local TV news, the top two leading subjects involved youth and violence and the third most frequent topic was accidents, often car crashes.102 Overall, the researchers found "twice as many discussions of crime and violence as there were of educational issues and student achievement."103 Among the 9,678 network and local TV stories the researchers analyzed, they found only nine "instances of teens praised for their involvement in community service or humanitarian work, and just six students who were singled out for their exceptional educational achievements."104

Once again, it is important to note that some crimes are worse than others. Homicide logically deserves more attention than delinquency or theft. But it is also important to consider the backdrop behind the homicide stories. When it comes to stories about youth, there is little else of consequence in the news. When news coverage about productive, nonviolent youth are the exception, not the rule, violence fills the void. Audiences without other contact with young people are particularly vulnerable to the perception that youth are violent and out of control. Crime and violence coverage may displace other types of coverage about children and youth, or diminish the importance the public places on children’s issues.105 The bias toward theft and violence may be influencing legislators to enact inappropriate policy as a consequence of believing the underlying messages in the news coverage.106 Further, when youth crime receives a far larger share of all crime coverage than youths actually commit, and when youth crime coverage dramatically increases while actual youth crime is decreasing, the public that relies on media coverage as its primary source of information about youth crime is misinformed.

Youth of Color Fare Worse than their White Counterparts. The one study that examined youth portrayals in magazines had the most to say about race.107 A qualitative analysis of all cover stories in Time and Newsweek between 1946-1995 determined that the term "young Black males" became synonymous with the word "criminal" during the late 1960’s when Blacks were struggling for equality. A March 1965 Newsweek article was the first to connect crime with Black crime. The first use of "young Black male" in a Time or Newsweek cover story was in 1970 when Time reported that "though victims of Black crime are overwhelmingly Black, it is chiefly young Black males who commit the most common interracial crime: armed robbery."108 The author argues that the story cemented the connection by focussing on Washington, DC, which had the highest proportion of Blacks in US cities and high rates of crime. Two years later Newsweek made the same connection. In later stories in the 1970’s, both Time and Newsweek portrayed crime as "largely perpetrated by ‘young Black males’".109 Later, Hispanic males were added to the picture. The author suggests that a combination of modern racism110 , media framing, and public discourse of crime as a problem of the Black urban poor has led to the racialization of crime, concluding that, as a consequence of news coverage, any discussion of crime today is essentially a discussion about race.

One study examined the speakers and speaking roles in local TV news stories about youth and violence.111 The premise was that young people speaking on the news are the images in the stories likely to leave the most lasting impression among audiences.112 The study found that youth seldom speak for themselves in any story. Although most stories about violence involve youth, the predominant speakers in stories were adults, usually men. However, with every violence-related role in which youth spoke — whether victim or witness of violence, victim or witness of threat, or criminal or suspect — youth of color were represented more often. By contrast, a higher percentage of White youths who spoke were in the role of victims of unintentional injury, a more limited and sympathetic role.

A study of youth crime portrayals in the New York Times revealed a similar imbalance. In that study, researchers found Black or Latino youth were never quoted directly while White youth were quoted in all five stories in which they appeared. Furthermore, defense attorneys for White youth were quoted 13 times but only twice for youth of color.113

Crime news is where all youth are most likely to be seen on TV news, but youth of color appear in crime news far more often than White youth – 52% and 35%, respectively. White youth were present more often in health or education stories (13%) than were youth of color (2%).114

In some cases, reporters may revert to stereotypes when they face language barriers or rely too heavily on one source. For example, in a qualitative analysis of 44 newspaper articles and 18 TV news broadcasts of a hostage-taking incident in a "Good Guys" electronics store, researchers found an emphasis on Asian gangs. The researchers discovered, however, that the young people were not gang members.115 For most of the news stories, reporters relied heavily on information from law enforcement officers who speculated inaccurately on the youths’ gang memberships and the spread of Asian gang activity in other communities.116

Youth Victims & Perpetrators. Only a few studies distinguished between youth victims and perpetrators. One found that homicide victims under age 15 received more coverage in the Los Angeles Times than would be expected based on the frequency of homicides in that group.117 Researchers examining the San Francisco Chronicle found more depictions of youth perpetrators than youth victims118 ; this finding concerned the researchers since youth are victims of crime at much higher levels than they are perpetrators of crime. Adults commit 1.5 times more violent crimes against juveniles than juveniles commit against each other; three times more children and youth are murdered by adults than by other juveniles.119

There was other evidence that youth perpetrators get more news attention than youth victims. In another examination of the Los Angeles Times researchers found that nearly one in four murder suspects (23.9%) whose ages were identified in the Los Angeles Times in 1997 were youth, while only one in six homicide arrestees (15.8%) in Los Angeles actually were youth that year.120 The overrepresentation of youth in homicide reporting occurred despite the fact the adult homicide arrestees killed more victims than their juvenile counterparts.

Violence Against Youth is Under-reported. Two studies assessed whether crimes against young people were being covered; both studies found that crimes perpetrated by adults against youth are under-reported.121 Several other studies that examined depictions of youth in the news generally did not detect substantial coverage on youth as victims of violence.122

The relative lack of reporting on violence against youth can be juxtaposed with the over-reporting of homicide by youth as compared to adults. In a comparison of youth portrayals in 327 stories from the 1997 Los Angeles Times (Orange County edition) to crime reports from the Los Angeles Police Department, researchers found youth homicides were nearly three times more likely to be reported in the Los Angeles Times, despite the fact that adults commit and are victims of far more murders. The authors conclude that the Times’ misplaced focus scapegoats youth, since they commit far fewer crimes than adults.123

Effects on Public Perceptions

A detailed study of the coverage of Denver’s "Summer of Violence," provides an opportunity to explore the influence the news media has on the public’s perception of youth violence.124 The study compared coverage of youth homicides in the Denver Post during the summer of 1993 to coverage in the summers of 1992 and 1994. The study also provides interviews with journalists, as well as elected officials and criminal justice personnel, to ascertain journalists’ motivations and impact on policy making during that watershed period for juvenile justice legislation in Colorado.

The study found that, while youth violence was a growing problem for many years in Denver, the news media shaped and highlighted the problem of youth violence during the "Summer of Violence" by giving high visibility coverage to several youth killings. This brought youth violence to the public’s attention, even though homicides by youth in Denver were slightly higher in 1991, 1992, and 1994 than in 1993.125 The Governor called a special session of the legislature that year and the legislature passed several punitive pieces of juvenile justice legislation, many of which had previously been considered and rejected.

After the "Summer of Violence" the news media moved on to other issues, and coverage of juvenile crime subsided dramatically, even though juvenile homicides increased the next year, and over the next summer. There was a 168.5% increase in the number of articles about youth crime between the summers of 1992 and 1993, and then a 220% decline in articles about youth crime in the summer of 1994, despite a 17% increase in the youth homicide rate in the summer of 1994 versus the previous summer. Similarly, there were 14 times as many "A" section articles in the summer of 1993 than in the summer of 1992 and four times as many in 1993 as in 1994. More than three times as many column inches were devoted to youth crime in the summer of 1993 as in either 1992 or 1994. Ultimately, the study concludes that it is not data, but news coverage, that galvanizes policy action about youth violence.

The Denver study shows us that heightened news coverage can focus attention and catapult policy action, a typical agenda-setting effect of the news. A second media effect, framing, can also have a profound impact on how news stories are interpreted by the public. Relevant here are experiments researchers have conducted to examine whether television news audiences respond differently to stories that include "mug shots" of alleged youth perpetrators of different races: Anglo, Asian, African American or Hispanic.126

In the experiments, audiences were chosen at random in a Los Angeles shopping mall to watch a news broadcast that contained a story with a close-up photo of an alleged murderer who was either a) African American or Hispanic; b) White or Asian; or c) no racial identity. A fourth control group saw a broadcast without a crime story. Researchers found that "a mere five-second exposure to a mug shot of African American and Hispanic youth offenders (in a 15-minute newscast) raises levels of fear among viewers, increases support for ‘get tough’ crime policies, and promotes racial stereotyping."127 While the stories with perpetrators of color increase fear among all viewers, White and Asian viewers have an increased desire for harsher punitive policies than African American or Hispanic audiences, who, the authors suggest, are reminded of injustice and prejudice by the crime stories. Thus, the authors argue, when mug shots of African Americans and Latinos are shown, local TV news crime stories expand the divide between racial groups. In a similar experiment, researchers found that students rated Black suspects as more guilty, deserving of punishment, more likely to commit future violence, and less likable than the White suspects, about whom they were given precisely the same information.128

Survey research on racial stereotyping and crime helps explain the experimental findings. Researchers have found that when Blacks are placed in a violent context, Whites who hold stereotypical attitudes that consider African Americans generally violent (and lazy) were far more likely to believe that the Blacks were guilty and prone to violence. But the same people did not have the same reaction if Whites were the ones placed in the violent context.129

Thus several researchers conclude that a discussion about crime in America is essentially a discussion about race.130 Evidence from a later study strongly supports that conclusion, as 60% of the people watching a news story without an image of a perpetrator falsely remembered seeing one, and in 70% of these cases they "remembered" the perpetrator as African American, even though they never saw him.131

The findings about race and crime catalogued in this report are eerily similar to research on news depictions of poverty. Martin Gilens compared network television and news magazine portrayals of poverty to who is poor in America, what Americans believe about the poor, and what those editing news photographs believe about the poor. He found that pictures in the news about poor people in America disproportionately feature African Americans, especially when depicting "less sympathetic" poor adults, as opposed to the working poor or the elderly.132 Gilens concludes that the disproportionate number of Black faces in news images about poverty may exist because network bureau and news magazine photographers largely operate in urban centers, where poor African Americans are more geographically concentrated than poor Whites. When the story assignment comes, photographers go where it will be easiest to take pictures of poor people – inner city African American neighborhoods.133 "Because poor Blacks are disproportionately available to news photographers," Gilens suggests, "they may be disproportionately represented in the resulting news product."134

However, Gilens notes that geographic concentration of African Americans in the inner city and photo editors’ own misperceptions of the overall distribution of race and poverty do not explain completely why there is such a preponderance of Blacks in news photos about poverty. Gilens maintains that some combination of photo editors’ own conscious or unconscious stereotypes, or their conscious or unconscious "indulgence of what they perceive to be the public’s stereotypes" explains the rest.135 In other words, photo editors choose photos with Black poor people in them because they think their viewers or readers will more easily interpret the photograph as being about poverty. Readers will recognize the familiar image, what they "know" to be true.

Crime news may suffer from similar factors of urban geographic concentration and stereotyping by news editors and reporters. Most youth violence in which youth are the perpetrators occurs in urban centers. In fact, in 1994, 30% of the homicides committed by youth occurred in just four cities – Chicago, Detroit, Los Angeles, and New York – cities which contained only 5% of America’s youth population.136 In 1997, 94% of counties in America had either one or no juvenile homicides, most of those being rural or suburban counties. Editors and producers may be making choices about which crimes to include that reflect their own internalized understanding of what crime consists of and what their audience cares about: violent Black perpetrators and White victims – the image that is being reinforced by selection choices. In most parts of the country, the primary news audience is White137 , a group that is statistically very unlikely to form their opinions about minority youth crime from personal experience. Those making news selections might assume that viewers and readers want to hear stories about people like themselves. If the news outlet’s audience, or target demographic, is primarily White, then editors and pro-ducers may "naturally" (that is, without critical examination) choose stories that feature Whites in sympathetic roles.

Journalists ponder why. There are reasons the coverage looks as it does. One is that crime news is easy – everyone knows what it looks like, how to gather it, and how to report it. Some journalists argue that audiences want news about violence, though most polls dispute that argument. Another reason is that news is a business, and reporters, producers, and editors have learned to choose the news they believe will draw the most attractive audience for advertisers.

The study of Denver’s "Summer of Violence" offers some insight into newsroom decision-making about which homicides warrant coverage.138 After interviewing editors, producers, and reporters, the researcher concludes that, in covering Denver’s "Summer of Violence" in 1993, journalists viewed these mostly White, middle class victims killed by minority youth through a predominantly White middle class lens. Denver Post reporter Steven Lipscher said, for example:

Take a look at our editors over there. Take a look at the news editors at the TV stations. Most of them are White middle class. Most of them are men but that doesn’t make a whole lot of difference here. They live in these nice middle class neighborhoods and when those neighborhoods start having random crime…and it gets close to the suburbs or even in the suburbs where these news editors live, you know that deeply troubles them. When the crime was centered solely on the inner city if we had minority editors, people who lived in the inner city, we might have covered it. But we didn’t and we still don’t. Inner city crime is not nearly as shocking as suburban crime and the only reason why is look at who is writing the stories and look at who is assigning the stories.

The White, middle class lens means that some murders are more important than others, as explained by this Rocky Mountain News reporter:

There are homicides and then there are homicides on the police beat. There are homicides I can work hard on and only get this much into the paper. And then there are the kind that all you have to do is mention to the editor, "Gotta former district attorney who just killed his wife," and we’re all over it…And as a colleague of mine once said, he had this theory that there were misdemeanor murders. That’s not a theory I subscribe to, but he had a point. Obviously, there are some murders that don’t count as much as others. A misdemeanor homicide according to Tony was typically a drug dealer [who] wipes out another drug dealer in an alley somewhere over a business deal gone bad. That is considered a low interest homicide (Emphasis in original).

Ultimately, individual news workers make decisions about what to include in the news of the day based on whether they personally care about the story. Reporters, editors, and producers have finely honed, internalized mechanisms that are triggered by their personal values and emotional responses, tempered by news judgement, experience, and expectations of audience response.139 Standard selection criteria for news stories – controversy, conflict, novelty, proximity, significance, timeliness, visual appeal, practicality – are processed through the personal filters of journalists.140

DISCUSSION

There has been concern about the effect of crime reporting on public understanding since long before television. The FBI crime index was created in the 1930’s in order to control the public interpretation of crime statistics via the FBI, specifically to avoid "the way the press seemed to manufacture ‘crime waves.’"141 Noncontextual news reports have also been long lamented. Thirty years ago, the Kerner Commission noted that "By failing to portray the Negro as a matter of routine and in the context of the total society, the news media have, we believe, contributed to the Black-White schism in this country."142

This analysis tells us that these concerns are still warranted. The studies reviewed here confirm that the news media’s cumulative coverage of youth, race and crime misrepresents crime, who suffers from crime, and the real level of involve-ment of young people in crime. With the consistent underrepresentation of White perpetrators and over-representation of Blacks and Latinos in violent crime stories, local TV news in particular regularly reinforces the erroneous notion that crime is rising, that it is primarily violent, that most criminals are nonwhite, and that most victims are White.

Non-representative portrayals of youth are especially problematic. The fact that violence against children and youth is a much larger problem than violence committed by youth143 has gone largely unreported by the news media.

The public relies on news for its knowledge of crime. We suggest that a "misinformation synergy" occurs in crime news that profoundly misinforms the public. The synergy results from the simultaneous and consistent presentation of three significant distortions in print and broadcast news. It is not just that African Americans are overrepresented as criminals and underrepresented as victims, or that young people are overrepresented as criminals, or that violent crime itself is given undue coverage. It is that all three occur together, combining forces to produce a terribly unfair and inaccurate overall image of crime in America. Add to that a majority of readers and viewers who rarely have any personal experience with crime by Black youth, and a White adult population who must rely on the media to tell them that story and we have the perfect recipe for a misinformed public and misguided power structure.

Each study’s findings, taken alone, may not be cause for alarm. After all, crime is a serious problem that demands news attention and political action.

But if news audiences are taking the crime coverage at face value, they are accepting a serious distortion. They are likely to believe that most crime is extremely violent and that perpetrators are Black and victims White. If news audiences have little contact with young people, they are likely to believe that youth are dangerous threats, in part because there are so few other representations of youth in the news to the contrary.

As noted in the Introduction to this report, the public believes just that. Seventy-six percent of Americans say they get their opinions about crime from the news.144 A 1998 poll found that nearly two-thirds (62%) of the public believes that juvenile crime is on the increase,145 even though there has been a 56% decline in homicides by youth between 1993 and 1998146 and the National Crime Victimization Survey reports youth crime at its lowest since that survey began (1973). Rather than informing citizens about their world, the news is reinforcing stereotypes that inhibit society’s ability to respond effectively to the problem of crime, particularly juvenile crime.

Journalists, too, are among the largest consumers of news. If the picture is distorted, it affects them as well. Reporters, editors, and producers making selections about what to cover are completely saturated by the images in their own storytelling. It appears that they have come to believe that the images they present on their pages and over the air reflect the world accurately.147

Since every news outlet can’t cover every crime, the question then becomes, how should reporters choose which crimes to cover? How can the overall picture be made more accurate? How can print and broadcast journalists make choices that minimize the distortions documented by researchers since 1910? How can their cumulative choices better reflect the crime and violence they cover? And when they make those choices, how can the media add more context to crime coverage so as to improve the viewers’ understanding of the causes and solutions to violent crime?

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE NEWS MEDIA Printable Version (pdf)

The overwhelming evidence is that in the aggregate, crime coverage is not reflecting an accurate picture of who the victims and perpetrators are. The most consistent finding across media and across time is the gross distortion of the types of crime reported in the news. Rather than informing citizens about their world, the news is reinforcing stereotypes that inhibit society’s ability to respond to the problem of crime, including juvenile crime. This is an admittedly difficult problem to fix, given the many constraints of daily journalism. Nonetheless, it is way past time to try to create a more accurate overall picture of crime, who suffers from it, and what can be done to prevent it. To begin to address this dilemma, we suggest that reporters, editors, and producers expand their sources; provide context for crime news; increase enterprise and investigative journalism; balance stories about crime and youth with stories about youth generally; conduct and discuss content audits of their own news; and examine the story selection process, adjusting if necessary.

Expand Sources

Reporters depend primarily on law enforcement or criminal justice sources for crime news. Several studies document the danger of limiting sources to criminal justice and police departments. Numerous analyses we examined show the misrepresentation that can occur when police statistics are reported unquestioned.148 Asian, Latino and Hawaiian youth, these studies found, were cast in stereotypical roles that did not reflect the population of youth, and misrepresented the level of gang activity. The lack of other non-violence-related portrayals of youth exacerbates this problem.

The dependence on traditional police sources hampers the full story on crime in at least two ways. First, the police benefit from some control over public understanding of crime statistics. Depending on the temper of the times, if they can show an increase in crime, they have reason for higher budgets. If they show crimes being addressed, they can engender public support. When efforts are made to count, the numbers go up, which may simply reflect unrecognized instances from before or a redefinition of old crime patterns to the new "countable" – and fundable – category.

This phenomenon was well-documented by Fishman (1980), who tracked a manufactured "crime wave" against the elderly that was created in part because the main source for information was law enforcement. After local police created a task force on crimes against the elderly, journalists tuned in, and were subsequently primed for stories on crime against the elderly. Fishman witnessed a process whereby news workers in a local television newsroom "manufactured" a crime wave by continuing to report on crimes against the elderly despite police statistics that showed an overall decrease in those crimes compared to the previous year. The close relationship between police and reporters propelled crimes against the elderly to the top of the media agenda. All of this means the journalists’ role as watchdog over public institutions and their ability to check police activity against other sources is important. They can only do that well if they have a good familiarity with sources other than law enforcement.

Second, police look good when the focus is on violent crime because they have a better record of solving homicide and sexual assault than they do with property crimes.149 For example, researchers found a 200% increase in crime prevention stories between 1980 and 1985 in Louisiana newspapers, mostly covering "Crime Stoppers" and "Neighborhood Watch" programs.150 They note the mutual interest police and reporters have in reporting like this. The police benefit from public acknowledgment of their work to prevent crime; reporters benefit by maintaining good relationships through such stories with police, whose access to crime information they need if they are to report breaking news.

A good example of journalists’ ability to expand sources occurred in the coverage of the shootings at Columbine High School. While official police reports were included in the Columbine coverage, the news media reached beyond law enforcement for interpretation and explanation.151 In the 12-month period prior to the Columbine shooting, criminal justice sources were quoted in 77% of stories; in the Columbine coverage they were sources in 45% of stories. In the Columbine coverage, the number of sources per story increased as we heard more from witnesses, independent experts, issue advocates, politicians, and youth themselves.152 The same questions journalists sought to answer after Columbine – How could something like this happen? What can we do to prevent it? – Can also be asked of a wider range of sources when more common violence happens locally.

Reporters should not cease using the police as sources for crime stories, but that should not be the only place they look. Some media researchers suggested that news organizations use interns to routinely query other sources for news, just as they do now with "beat checks," the calls made routinely to police stations.153 Law enforcement perspectives limit the questions a reporter might pursue. Most crime beats are focused on cops and courts and the details of a specific event. Reporters are focused on what happened, and whether the perpetrators have been apprehended. Community-based sources, public health departments, and others have data and information that can balance a law-enforcement-only approach. For example, hospital admission data, though not always available for a breaking story, can help reporters put crime and its consequences in perspective. Health departments and coroner’s offices are good sources of homicide data. Other social agency employees and community residents can have information about neighborhood life pertinent to crime stories. Reporters need to cultivate these sources the same way they cultivate the local beat cops.

Provide Context for Crime News in Regular Reporting

Robert Entman suggests that local television attention to crime is a function of news workers’ need to appeal to a wide audience that crosses political jurisdictions. TV uses violent crime stories to arouse emotions rather than presenting analyses to help people deliberate local policy choices because emotional reactions are the same across political boundaries, though policy may be different.154 Thus reporters are drawn to homicide because everyone in their audience can appreciate the drama. But interpreting violence narrowly in terms of homicide, and interpreting homicide in terms of personal altercations or failure of restraint misses the larger story of violence. For example, in a study provocatively titled, "Violence in American cities: Young Black males is the answer, but what was the question?," racial differences for homicides disappeared when researchers controlled for "marginal urban landscapes," defined specifically as proximity to LULU’s (Locally Unwanted Land Uses, such as waste incinerators, landfills, airports, refineries, etc.) and TOADS (Temporarily Obsolete Abandoned Derelict Sites, such as deserted factories, power plants, mines, vacant garbage-strewn lots, etc.).155 Local disintegration is the key risk factor for violent death, not age or race.156

Certainly excellent reporting on this issue has been done157 , but in general, the studies here confirm that it is the drama of single crimes that is regularly made vivid, not the links to larger social and physical environments and precursors.

By context we do not mean the particular details of an individual crime (the "blood-soaked shirt" and the like). Instead we are referring to the relationship of the single incident to the larger social fabric, be that neighborhood conditions, the risk factors for violence, or crime rates – all the things that help explain the status of crime, race and youth. The challenge is to add the social context to the storytelling and give audiences some guideposts for interpreting the crime.

For example, no reporter would investigate a car crash scene, late at night, and not ask whether the driver or passengers had been drinking. It is an appropriate question because alcohol is a known risk factor for vehicle crashes. But alcohol contributes to homicide at almost precisely the same rate it contributes to fatal car crashes – 32% and 33% respectively.158 If it make sense to ask the question, "Was alcohol involved?" At the scene of a crash, it makes sense to ask it at the scene of a crime. Questions generated from the risk factor research on violence can help crime beat reporters ask better questions. Then they could link specific crimes to larger issues and prevention. For more than 15 years, epidemiologists have been identifying violence risk factors, including the availability of firearms and alcohol, racial discrimination, unemployment, violence in the media, lack of education, abuse as a child, witnessing violent acts in the home or neighborhood, isolation of the nuclear family, and belief in male dominance over females.159

Another explanation print and broadcast journalists could offer for the picture of crime reported here is that they focus on the unusual – that the unusual is what, in fact, makes the crime stories newsworthy. While this might be true, it does not explain the absence of context that would help citizens understand how to interpret the rare event. In other areas of reporting, integrating context is expected. In almost every area of a newspaper or broadcast – sports, business, politics, entertainment – general information is integrated with spot news and events are made sense of for audiences by placing them in a larger context, if not in the same article, then with additional graphics or sidebars or standing reports. With every other topic, newspapers are including information that depicts the status of issues, along with the unusual events.160 Stories on crime and youth could be treated with equal depth and breadth.

There is some evidence that including context as we’ve defined it here makes a difference to news consumers. In a 1993 experiment, researchers found that when accidents were reported with more attention to the "causal chain of events, described in the human context of antecedents and aftermath, and weekly accounts of local accident statistics were given (including date, location and severity)," then newspaper readers’ had a better understanding overall of accidents’ relationship to other community issues.161

An excellent example of providing context occurred with the Washington Post’s coverage of a 2000 shooting in Mt. Morris Township, Michigan, of a six-year-old girl by a six-year-old boy. To be sure, the Post covered the tragedy, as did most papers, the day it occurred. But four weeks later, the Post ran an extensive, front page article on the factors that contributed to the boy’s involvement in the shooting, including the impoverished neighborhood he lived in, his ready access to guns, and the neglect he received at the hands of his drug-involved caretakers – all factors which are highly associated with violence.162 Other reports connected the consequences of welfare reform to the incident, since the boy’s mother had been forced back to work despite the lack of adequate child care arrangements for her son.163

Providing context means that news organizations must reinvest in the practice of journalism. Resources must be available so that journalists can do the work to understand the landscape of violence in the region they cover. Reporters need time to cultivate relationships with key sources, get to know neighborhoods, and do "gumshoe" journalism. It takes much more work, and time, on the part of reporters to draw out the drama in those stories and connect them meaningfully to the larger context. News organizations need to support this time, which leads to our next recommendation.

Bolster Enterprise and Increase Investigative Journalism

Reporting the unusual is of interest to reporters and the population at large. But a news focus almost exclusively on the unusual has detrimental consequences. First, to the uninitiated news consumer, those unaware that reporters and editors make a series of choices about what goes into the newspaper or TV broadcast, the regular diet of unusual over time seems usual. If the only information people receive about crime, violence, and youth is from the news, it is not surprising that they would think the world is an increasingly dangerous place, and that African Americans are more likely to victimize Whites than are other Whites. If the few studies of youth in the news are correct, the public learns that young people are more violent than ever before, that most youth are violent, and that people under age 18 commit almost as much violent crime as adults do. Yet none of these conclusions is true.

Instead, reporters should be telling stories about typical events, and telling them with more depth. Continuous coverage of rare events, even with a disclaimer alerting news consumers about the rarity, is not sufficient.

The remedy is enterprise journalism. Enterprise journalism means reporters don’t work from news releases or police scanners, but get out from behind their desks, into the community, where a variety of sources and perspectives can be reported. Reporters can then do the digging to find true exemplars of real trends, rather than chasing the easy, but rare, high profile event.164 They can enlist organizations such as the National Institute for Computer-assisted Reporting which can help with collection and analysis of trend data. Then they will know what they are looking for, and be able to recognize a potentially newsworthy event —— newsworthy because it is a good example of the real problems the region faces, not because it is rare. News pro-ducers hope their audiences will connect with the human drama of the story, and the human drama exists in the routine violence as well as the unusual. It simply requires good reporting to uncover that drama.

Investigative journalism – digging deeper, over longer periods of time – can help uncover important stories and explain new trends. It holds the potential to reveal juvenile crime stories that have gone completely unnoticed by the general public. For example, in its award-winning series on abuses at the state’s boot camps, the Baltimore Sun awoke state leaders and citizens to abuses at the camps and lax after care of delinquent youth upon release. The result – five top juvenile justice officials lost their jobs, the boot camps were permanently closed, and the Department of Juvenile Justice received its largest single-year budget increase in history.

Balance Stories about Crime and Youth with Stories about Youth in General

News organizations must pull back their lens to get a broader picture of what else young people are doing. When it comes to youth, violence is as prominent in the news as education.165 Portraying the two subjects nearly equally exaggerates the rate of violence and gives short shrift to education, particularly since 52 million young people go to school but only 125,000 are arrested for violent crimes each year. What issues affect them? What other newsworthy activities are they engaged in? Without such coverage to balance reporting on crime and violence, the public sees a narrow, inaccurate reflection of youth.

Journalists themselves are reaching this conclusion. In an extensive article on how youth are covered in newspapers, Los Angeles Times reporter David Shaw documented similar critiques – and self-critiques – from journalists around the country. Experts on children and journalists themselves noted that children’s issues are undercovered and audiences underserved as a consequence. "Traditionally," writes Shaw, "most children have been in the news only when they’ve done something bad or when others have done bad things to them. Even though most kids don’t fit into either category, this coverage can adversely – and unfairly – influence public perceptions and public policies that affect children, especially teenagers."166

To remedy this, some news organizations have created special beats to cover children and youth. Organizations like the Casey Journalism Center for Children, Youth, and Families at the University of Maryland provide training for reporters and editors on key issues. NewsLab, a project affiliated with the Project for Excellence in Journalism, provides suggestions for reporters who want to bring more substance and better storytelling to local TV news. And, young people themselves have made reasonable suggestions that would result in more comprehensive coverage. In San Francisco, the UNYTE Youth Team, after careful study of youth depictions in the San Francisco Chronicle, suggested that the news media could balance crime coverage of youth by:

- presenting news reports about youth crime in proportion to crime that youth commit;

- producing in-depth stories that connect the conditions and underlying causes for crime among youth;

- hiring youth reporters for youth issues and soliciting youth commentaries for editorial pages;

- linking the consequences of policy decisions to conditions and events involving youth (e.g., critically examine the effectiveness of incarceration policies);

- reporting on the link between poverty and violence; and

- involving young people in monitoring their coverage of youth.167

Heeding this advice may have the added value of attracting younger audiences to the news.

Conduct Internal Audits of the News

Print and broadcast journalists can compare their outlet’s news reports to actual trends in the region they cover. What are the data on race, age, and gender in relation to violence? Based on the news, would regular readers and viewers see an overall distorted picture of crime, race, and youth? News organiza-tions can and should examine and publish their own statistics on the race, age and gender of offenders and victims they re-port on and let readers and viewers know how that compares to other indi-cators from criminal justice or public health sources. Such analyses can foster pro-ductive newsroom discussion and spawn mechanisms for correcting the cumulative distortion of story choices. Publishing the analyses can also educate audiences to be better consumers of the news.

When a newspaper pays attention to how it portrays a group or an issue, and makes a concerted effort to change, it can end up with a better news product. For example, the Los Angeles Times succeeded in expanding the roles in which Latinos appeared in the paper after careful content analysis and in-depth discussion in the newsroom.168 Using an innovative newspaper content analysis, reporters and editors were able to identify serious limitations in the way Latinos appeared in the paper. The research helped reporters and editors understand the deficiencies of their own reporting, and the paper was willing to hire a special group of reporters to focus on Latinos in Los Angeles. The results from the Times are promising. After months of work, Latinos now appear in the paper more frequently and in a greater diversity of roles, rather than being concentrated in low-income or criminal depictions as they were previously.

Examine the Selection Process, and Exercise Restraint When Necessary

Sometimes, the news media should not cover certain stories, or not cover them prominently, because they inflame but do not inform. Of course, news outlets cannot stop telling unusual stories, but they need not tell every one, thereby overwhelming readers and viewers with a cumulative misrepresentation, especially when it means there is not room for less sensational but more important news.

Some news organizations have already begun to apply criteria for story selection, like KVUE-TV in Austin, Texas, which does not air crime stories unless they meet one of the following five criteria:

- Does action need to be taken?

- Is there an immediate threat to safety?

- Is there a threat to children?

- Does the crime have significant community impact?

- Does the story lend itself to a crime prevention effort?

KVUE-TV applied these criteria and remained the top-rated news program in its market. Following the shooting in Springfield, Oregon, the Chicago Sun-Times editorialized that it would no longer cover out-of-state shootings on its front page out of concern that the prevalence of such shootings was being exaggerated and would frighten children. The New York Times’ coverage of the shooting in Mt. Morris Township, Michigan on March 1, 2000, ran on page A14, given equivalent space and prominence with a study on racial disparities in school suspensions.

Who Gets Attention in the Newsroom?

Is perceived victim "worthiness"169 the unspoken criteria for whether a murder is selected for the news? Reporters should ask themselves: Who qualifies as a worthy victim in my newsroom? Who doesn’t? By making these criteria explicit and sharing decisions with readers and viewers, reporters will give them some indication of what they are choosing from, what the field of possibilities is on a given day or in a given week.

If reporters limit themselves to reporting what just happened without considering how that crime fits into larger patterns, the news is doomed to be distorted. The best reporters can do in that situation is say, "This is unusual." However, in the absence of a picture of the usual, the repeated image of unusual crimes will fill the void. One way out of this trap is to be sure the newspaper, magazine, or broadcast turns as much attention – or at least some – to the usual victims and perpetrators of crime. If, for example, domestic violence is a frequent type of assault in the area the outlet covers, or if child abuse is a frequent cause of death for young people, journalists should report on that at least as frequently as other types of assaults or homicides.

The special case of race. In particular, reporters should ask themselves whether the race of the victim or suspect determines whether a story gets reported. One researcher noted that a Chicago newspaper reporter told him that "his newspaper considered news of Negro crime to be ‘cheap news’," especially when both the victim and suspect were Black.170 In another study, four White reporters interviewed believed race played no role in story selection, while the Black reporter who was interviewed believed race did play a role.171 All the reporters interviewed equated race with location (inner city versus suburbs).

Editors and producers may choose to give space to certain crimes over others because of who in their audience is affected. Writing in Editor & Publisher, veteran journalist Nat Hentoff suggested that we don’t see much reporting of victims of color because "too many newspapers treat such crimes as so ‘routine’ as to be not worth the space to report on them."172 The research reviewed here reveals a more complicated picture: It’s not just that victims of color are less visible, but also that suspects of color are more vividly depicted. Race has powerful salience in news and is worth special attention in newsrooms. Discussion about crime and race among journalists has primarily been centered around whether or not racial identifiers are appropriate in stories describing suspects.173 Recommendations have included being sure the racial reference is relevant, explaining that relevance, avoiding euphemistic adjectives (e.g., "inner city"), using racial identifiers only when they add value to the story, and being informed generally about people of races other than one’s own.174

There is some evidence that news consumers remember more about what they see than what they hear.175 Iyengar, for example, found that TV news viewers were more likely to attribute responsibility for fixing problems to government and institutions after they watched TV news stories that included contextualizing information, except when the story focused on an African American.176 In that case, viewers attributed responsibility for fixing the problem to the victim. Race trumps everything else in news stories as viewers revert to demeaning and inaccurate stereotypes. Gilliam and Iyengar refer to this as the "crime script", the expected sequence of events from which news consumers derive meaning and draw conclusions based on their experience with previous or similar events. When it comes to crime, they argue, television news has taught viewers that the pattern to expect is "crime is violent, and criminal behavior is associated with race/ethnicity."177

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR CHILD ADVOCATES, YOUTH GROUPS AND CIVIL RIGHTS ORGANIZATIONS Printable Version (pdf)

While most of this report and these recommendations have focused on what the news media can and should do to improve crime coverage, there is much that juvenile justice advocates can do to help generate a fairer depiction of youth crime. Journalists make the ultimate decisions about what stories will be told and how the information will be conveyed. But journalists rely on their sources for information, verification, and explanation. If those with the most information about and access to young people refuse to talk with journalists, the picture of youth on the news will be incomplete. We recommend that advocates build relationships with journalists, talk to them about their coverage, and help them get the information they need to do more complete stories, be it hard data or young people to interview.

Work With Reporters To Give A More Accurate Picture

Because of the juvenile justice system’s historic confidentiality protections, many child advocates refuse to talk to reporters about the context of individual cases. This places a serious and sometimes insurmountable burden on reporters when they try to tell a more complete story. It can also result in monolithic depictions of young people as criminals whose delinquency is presented without important contributing antecedents.

Over the past decade, 43 states have diminished confidentiality protections, so that the news media now have unprecedented access to information about delinquency proceedings. Defense attorneys and child advocates must learn new ways to work with members of the news media to allow a fuller story to be told about troubled young people, without abandoning confidentiality protections. Over the past year, conferences held by the American Bar Association’s National Juvenile Defender Center and the National Legal Aid And Defender Association have sought creative ways to do just that. Other resources are available for advocates interested in better understanding the constraints of the news business and improving their skills in communicating with reporters.178

Engage Reporters, Editors, and Producers In Dialogue About Their Coverage

Child advocates, youth groups and civil rights groups need to begin to engage news outlets as consumers to educate the news media about their needs and to jointly seek solutions to the complex issues raised in this and other reports about coverage of youth crime. We Interrupt This Message, an advocacy group that conducted two of the studies discussed in this report, took its findings on disproportionate youth crime portrayals directly to the San Francisco Chronicle and the New York Times. In 2000, Suffolk University’s law school held a forum which brought together reporters from the Boston Globe, the Boston Herald, and several electronic media with lawyers and community groups that work with young people for a productive exchange of ideas about coverage of youth crime. In recent years, civil rights groups like the NAACP and the National Council of La Raza have highlighted the scarcity of minority representation on network programming. Although these efforts concerned entertainment media, similar efforts to educate news media about depictions of minority offenders and victims may also be well received.

Make Data Available

Journalists need local data to make national problems relevant for their audiences. Share information with journalists so they can learn about local patterns, incorporate that information into daily stories, and give citizens the information they need to make better decisions about violence prevention policy.

Prepare Young People To Speak for Themselves, and Let Them Do So

Youth are becoming involved in advocacy efforts about juvenile justice and violence prevention from coast to coast. Give young people the training and support they need to speak confidently about the work they are doing to improve their communities for themselves and others. Increasing the visibility of young people in the news will help balance the current picture. Create situations where young people can interact with journalists so they can begin establishing themselves as sources on their own.

Make Yourself Available to Reporters

Youth advocates and researchers cannot have an impact on the coverage of youth crime if journalists don’t know they exist, if they cannot find spokespeople when they need them, or if advocates do not respond to their requests for information in a timely manner. Sometimes, this will be difficult, because breaking stories about youth crime do not always arise at convenient times. But advocates’ availability as experts or alternative voices prior to deadline can help shape coverage and put violence among youth into its proper context.

CONCLUSION

If the public and policy makers have internalized a distorted picture of crime, race, and youth from the news, journalists are likely to have done so as well. After all, journalists consume more news than anyone. A quick trip to any newsroom makes that instantly clear: Twenty-four hours a day journalists are under pressure to be aware of current news or anything that might become news. To meet the pressure, news organizations stay tuned in to each other, via the wire services, radio, print, or TV, which is available in newsrooms overhead and in every direction. News organizations watch each other closely, and mimic each other’s news. Unfortunately, many of them are repeating a terrible distortion. In whatever way they can, reporters have to break through complacency and question their own news and news gathering habits. When it comes to young people, race, and crime, readers and viewers require a more complete accounting of what is happening to whom. Without print and broadcast journalists’ better efforts, the public will never know enough about why violence happens, what is happening to prevent it, and what, as a society, we should do next.

ENDNOTES

1 Males & Macallair 2000

2 Jones & Yamagata 2000

3 Juszkiewicz 2000

4 US OJJDP 1999

5 Pope & Feyerherm 1995

6 Bridges & Steen 1998

7 The National Crime Victimization Survey is an annual survey of over 40,000 Americans inquiring about victimizations they have experienced in the previous year. It is generally considered highly reliable by criminologists because, unlike the FBI's Uniform Crime Reports, it does not rely only on crimes that become known to police, and therefore is less affected by differential rates of citizen reporting over time.

8 Belden, Russonello & Stewart, 1999

9 Brooks, Schiraldi, & Ziedenberg 1999.

10 When asked "Who commits most of the violent crime these days?" 60 percent of respondents chose young people (Fairbank, Maslin, Maullin and Associates and the Tarrance Group, conducted for The California Wellness Foundation, May 1996). In California in 1996, juveniles made up 13% of the state's violent arrests, according to the California Attorney General's Office.

11 Males & Macallair 1999

12 Snyder & Sickmund 1999

13 Updegrave 1994

14 Lippmann [1922]1965

15 ABC News 1996

16 Braxton 1997

17 Farkas & Duffet 1998

18 quoted in Farkas & Duffet 1998

19 cf. McCombs & Shaw 1993

20 Snyder & Sickmund 1999

21 see Oliver 1994

22 Though we did our best to make the database search exhaustive, there is no way to ensure that 100% of relevant studies were captured in our search. The authors would appreciate any information on published studies that are not referenced in this report.

23 Local law enforcement statistics cited in this report include data from the Chicago Police Department and the California Department of Criminal Justice.

24 We found no studies of crime on radio news.

25 Sheley & Askins 1981

26 We did not include studies published in languages other than English or about news distributed outside the US However, several studies turned up in our literature review that indicate the patterns in other countries are similar to the findings described here (c.f. Williams and Dickinson 1993). Fishman and Weimann (1985), the only study we found with a detailed examination of crime and gender on the news, investigated how women and criminality were portrayed in the major Israeli daily newspapers. They found that gender depictions vary with different crimes, and when stereotypes about gender roles are violated, news reports use lenient language that treats female victims as "exceptional," perhaps reinforcing stereotypes about aggression in women and men.

27 Subervi-Vélez 1999

28 Chavez and Dorfman 1996-7

29 Vargas and dePyssler 1999

30 Turk et al. 1989

31 Dorfman et al. 1997; Gilliam et al. 1996; Klite 1998a, 1998b, 1995b; Bliss 1994; Romer et al. 1998

32 Center for Media & Public Affairs 1999, 1997a, 1997b, 1997c, 1996, 1995; Dominick 1978

33 Grabe 1999, Barlow 1995, Windhauser et al. 1990

34 Antunes and Hurley 1977

35 Davis 1952

36 Sheley and Ashkins 1981

37 Chermak 1998

38 Johnstone et al. 1994

39 Sorenson et al. 1998

40 Sorenson et al. 1998

41 Gilliam et al. 1996:10

42 Barlow et al. 1995

43 Center for Media & Public Affairs 2000a

44 Center for Media & Public Affairs 2001

45 Klite 1998a, 1998b, 1995a, 1995b

46 Kaiser Family Foundation 1998

47 Barlow 1995

48 US Department of Justice 1999

49 US Department of Justice 1999

50 Braxton 1997

51 Krajicek 1998:42

52 Bliss 1994, Dorfman et al. 1997, Dorfman & Woodruff 1998, Fenton 1910, McGill N.D., McManus & Dorfman 2000, Perrone & Chesney-Lind 1997

53 Barlow 1998

54 US National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders 1968

55 Klite 1995c:4

56 Romer et al. 1998

57 See the University of Missouri School of Journalism's Guide to Research on Race and the News for a comprehensive catalogue of all aspects of research on race and the news (beyond the crime and violence category).

58 Dulaney 1969

59 DeLouth & Woods (1996) found that when suspects were from an ethnic minority group, disclosure of the victim's ethnicity (most often White) was more common. However, the authors cautioned that their numbers were too small to be conclusive.

60 Barlow 1995, 1998; Dulaney 1969; Gilliam & Iyengar 2000; Gilliam et al. 1996; Entman 1990; Grabe 1999; Romer et al. 1998; and Weiss and Chermak 1998 all found minority overrepresentation of perpetrators; Fedler and Jordan 1996; Rodgers et al. 2000, and Sorenson et al 1998 found no overrepresentation of minority perpetrators.

61 Hawkins et al. 1995, Johnstone et al. 1994, Pritchard & Hughes 1997, Romer et al. 1998, Sorenson et al. 1998, and Weiss & Chermak 1998 all found Black victimization underreported compared to Whites; only Fedler & Jordan 1996 found no disparity.

62 Romer et al. 1998, Smith 1991, Johnstone et al. 1994, Sorenson et al. 1998

63 Pritchard & Hughes 1997

64 Weiss & Chermak 1998

65 Sorenson et al. 1998:1514. Note: Sorenson et al. controlled for the overwhelming frequency of stories about the O.J. Simpson murder trial by counting all Simpson stories as one.

66 Weiss & Chermak 1998

67 Klite 1995a

68 Klite 1995b

69 Gilliam et al. 1996

70 Gilliam et al. 1996

71 Entman 1990, 1992, 1994a

72 Entman 1992

73 Romer et al. 1998:296

74 Romer et al. 1998:298-9

75 USGAO 1990

76 Updegrave 1994

77 Romer et al. 1998 NOTE: Romer et al. used the FBI rate for homicides to compare to the vicitimization in crime stories (not just homicide stories). Their comparison is not exactly parallel, but we have included it here because homicides dominate media crime coverage, and because in other categories of crime Whites are more likely to be victimized by other Whites, though at a lower ratio than for homicide.

78 Sorenson, et al. 1998

79 Entman 1990

80 Rodgers et al. 2000

81 Pritchard 1985

82 Fedler and Jordan 1996

83 quoted in Fedler and Jordan 1996

84 Greenberg et al. 1983

85 Greenberg et al. 1983