Questionable Police Shootings: Why They Persis By Thomas J. Aveni Staff member, The Police Policy Studies Council Recent events have again dramatically illustrated that law enforcement has yet to address its most problematic issue. There is no consequential parallel in contemporary law enforcement to the perception that police have misapplied deadly force. The riots in Cincinnati are only the most recent example of the dynamics of this phenomenon. While civil disorder rarely seems an outgrowth of any other form of perceived police misconduct, in this era of identity politics, it has become all too commonplace when officers use deadly force. Adding to the volatility of this issue is the evolution of highly organized political enterprises that have prospered from such tragedies. The perception that police routinely misuse deadly force as a manifestation of class or racial oppression has galvanized what seemingly began as a grassroots movement. Today, a web-based search of phrases such as, “police abuse,” or “police brutality” will not only transport your attention to a myriad of the usual ultra-Left political entities, but it will also land you upon the doorstep of diverse libertarian and anarchist organizations as well. It is not the intent of this article to examine the political agenda of the diverse groups that have attempted to seize upon this issue. Rather, it would be infinitely more constructive to explore the underlying causation of questionable police applications of deadly force, and from there develop mitigating strategies based upon what we know with reasonable certainty. Our first order of business must be to find an agreeable definition of what a “questionable” police shooting is. The definition we’ve adopted is as follows: “When the suspect shot by police was unarmed and not-assaultive at the time he/she was shot.” This definition should not be construed to suggest that these circumstances automatically deem the shooting as a “bad” one, but rather, these particulars would suggest that closer, objective evaluation was warranted. Unfortunately, the only studies that have been done regarding the frequency of unarmed suspects being shot did NOT factor in whether the suspects were “not-assaultive” at the time they were shot by police. Worse yet, the only studies we have found addressing the issue of suspects being unarmed when shot are all pre-Tennessee v. Garner case studies. Any studies done prior to the Garner decision would be skewed significantly by the fact that many states provided statutory authority for officers to shoot unarmed “fleeing felons” until the U.S. Supreme Court restricted this procedure with its 1985 Garner decision. The studies that were conducted with pre-Garner data suggested that from 25% to 43% of suspects shot by police “appeared” to have been unarmed at the time they were killed. As you know, the number of suspects shot by police has declined dramatically since the 1985 Garner decision. While no hard data yet illustrates what impact the Garner decision has had upon the frequency of “questionable” shootings, it would be reasonable to assume that the elimination of statutory authority to shoot anyone fleeing the scene of a felony has placed a premium upon shooting only those who seem to be posing an imminent lethal threat to human life. It is upon this paradigm shift that we believe the prevalence of questionable police shootings has declined even greater than the aggregate rate of decline of all police shootings. The actual number of questionable shootings may now, by our best estimates, be within the 10-15% range. This by no means suggests that the problem doesn’t remain egregious. Recent events underscore the seriousness of this residual problem. The challenge facing police administrators, supervisors and trainers alike is that what progress we have made post-Garner is analogous to the first few pounds one loses when initiating a weight-loss regimen. To mitigate the remaining numbers of questionable shootings will require far more research, as well as considerably more thought and committed resources. There are some glaring associative issues that we can target with immediacy. For instance, we know with certainty that most police shootings occur during hours we associate with diminished lighting. Look at any ten-year UCR aggregate of officers killed, and you’ll find that the roughly 2/3’s of officers killed and nearly ¾’s of officers feloniously assaulted occurred between the hours of 6:00PM and 6:00AM. While some agencies have committed some resources to having their officers “qualify” with firearms in low light conditions, little if any thought has been given to addressing the cognitive impairment officers are routinely expected to render critical decisions with.

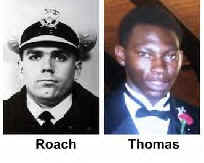

From Cincinnati, in officer Steven Roach’s shooting of suspect Timothy Thomas, to the New Jersey Stanton Crew incident, the Chicago Latanya Haggerty incident, to the cataclysmic Amadou Diallo shooting, one of the most common threads you’ll notice with but a cursory glance is that decision-making at night is extremely problematic.

The acuity of human vision is completely predicated upon the availability of ambient light. Without adequate light, we may find ourselves as visually impaired as someone deemed to be legally blind. In effect, officers are routinely required to make life-or-death decisions with a level of visual impairment in excess of what they’d be allowed to legally operate an automobile with. Since vision is largely a function performed within the brain, what data isn’t being received visually (as in poor lighting conditions) is often interpreted from the context in which we “see” things unfold. Suspects often illustrate physical cues that we might associate with past experience and/or training. Thus, what we think we see in a low light environment isn’t necessarily what actually is. As a consequence, our expectations of what we might see could very well influence what we think we see. To put this all into a graphical perspective, we’ve designed a chart in an attempt to illustrate how many Lethal Force Events (LFE) transpire. Since no two LFE’s are exactly the same, this illustration attempts to incorporate some situational elasticity.

When an officer-involved shooting is later examined (e.g., by investigators, the media, grand jurors, etc), it is scrutinized to the extent that we question whether an officer’s judgment was rational and prudent at the time deadly force was applied. However, the stress associated with a life-threatening event can trigger a neurobiological reaction that commonly short circuits the rational decision-making apparatus of the brain, placing the officer in a reactive state of neurological function. Some refer to this emotive neural trigger as an, “amygdala hijack.” In effect, events examined within the sterile context of an investigation seldom yield evidence of what the officer experienced at that critical juncture. Expert counsel should be sought from clinical psychologists with experience in this area, even to the extent that this asset becomes integral to the investigation of an officer-involved-shooting (OIS). Further complicating threat identification is the fact that a deadly force threat can manifest itself in a fraction of a second. As our research, and other parallel research has shown, the officer cannot react as quickly as an assailant can act. Our preliminary studies have led us to believe that if the officer waits until a threat has manifest itself as being immediate, he’ll generally return fire .365 seconds AFTER his adversary has fired --- if the officer manages to return fire at all. The degree of compounded cognitive difficulty stems from the fact that as a threat evolves, it often evolves as a consequence of rapid and sometimes veiled movement on the part of the suspect. The rapidity in which the threat unfolds determines the degree of visual and cognitive difficulty, as the human eye doesn’t actually see rapid movement. Rather, what we see is a composite of that movement, and it generally looks as if the movement is a “smear” rather than being anything definitive. If the initial stages of the threat evolved while “veiled,” the officer might only “see” the culmination of the suspect’s actions. For example, if a suspect had his back turned towards an officer, and was extracting a handgun from his waistband, presentation of the handgun would only become apparent as the suspect turned to point and fire at the officer. Our research indicates that a suspect can readily turn 90 degrees and fire a handgun within .31 seconds. Again, waiting for fulfillment of the “immediate threat” standard always puts the officer behind the survival curve

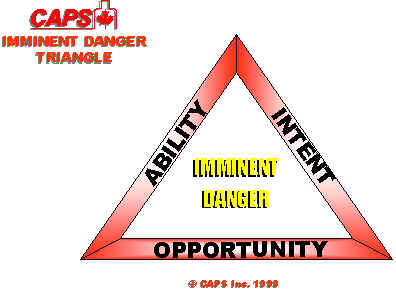

It is for this reason that agencies must examine terminology within their own

deadly force policy. Our lexicon is severely challenged when attempting to

articulate when we can judiciously extinguish a human life. We often employ a

graphical illustration (as with the CAPS “Imminent Danger Triangle”) of

policy in the hope that officers might better conceptualize what the words mean. The words “imminent” and “immediate” are often used interchangeably. In most applications, the difference is innocuous. However, as these terms are used to constrain the circumstances in which deadly force might be utilized, they are decidedly different. An “immediate” threat could be characterized as if one were faced with an adversary slashing a knife at him within contact distance. On the other hand, an “imminent” deadly force threat would be if that same adversary were charging at the officer with that knife from across a large room. In these examples, proximity is the only distinction, as a deadly force response by the officer would generally be justifiable in both cases. In application, if offered the choice, one should prefer to deal with an imminent lethal threat rather than an immediate one. The problem arises when we consider the fact that the vast majority of police lethal encounters occur at very close range, and to therefore compel an officer to wait for manifest “immediacy” of a lethal force threat would be tantamount to suggesting that the officer’s life is expendable. Mitigating strategies can be complex, but some short-term remedies do offer substantive results. We’ll offer some simple suggestions within the realm of policy and procedure. Be mindful of the fact that training is the enabling tool of policy implementation. Policy Recommendations Policy should stress the fact that while the apprehension of criminal suspects is a vital element of the job, it is always secondary to officer safety. This may seem too evident to be addressed, but there is an alarming scarcity of written policy and force continuums that express this sentiment. With all too familiar frequency, it is when officers see criminal apprehension or contraband seizure as their paramount concern that they place themselves in precarious situations. This is a frequent causal factor in needless officer casualties, as well as questionable shooting of suspects. Officers must also be compelled to carry an illumination device at all times, even when working a day watch. This needn’t be burdensome, as there are many small yet powerful lights that mount comfortably to the belt. Policy and training should reinforce the notion that the flashlight is generally deployed long before the firearm is. Critical errors in decision-making under adverse light conditions would generally be minimized with such protocol. In addition, officers won’t generally walk into a situation that is transparently untenable if they have sufficient light to make that assessment. Any officer-involved shooting that has occurred under low light conditions should have those conditions accurately quantified. It is insufficient to state that the lights conditions were “poor.” Poor, by who’s standard? Investigators should be equipped and trained to use quality illuminometers for this purpose. Light conditions so quantified would better enable a visual expert to determine whether the officer’s degree of visual ability contributed to proper or erroneous judgment. While the courts are often the arbiter of deadly force issues, methodical crime scene light measurement should pay dividends in the pursuit of objective reasonableness. Training Recommendations Officers must be trained to search with the flashlight in a manner that will earn their confidence. They must be taught that while there is a dearth of documentation of officers being killed while using their flashlights, there is ample evidence of officers either being slain by what they didn’t see, or shooting unarmed suspects they couldn’t accurately identify. It is also imperative that officers be trained to search independently of their muzzles. Many firearms instructors purposely train their officers to search with the handgun and flashlight “married-up.” This procedure should only be used when the officer is either verbally challenging a potential threat, or when the officer is committed to firing his/her weapon. Remember, if you train your officers to, “never cross anything with your muzzle that you aren’t willing to destroy,” searching with flashlight and gun married-up represents a serious training conflict. Unintentional firearms discharges appear to be far more frequent in low light scenarios. How you train your officers to negotiate low light scenarios can either mitigate or exacerbate the problem. Final Thoughts It must be conveyed to officers that their physical safety should always come before criminal apprehension or contraband seizure. The police drive to apprehend can be likened to the “prey drive” of most dogs. A dog will generally chase a thrown stick into oncoming vehicular traffic, and an officer focused on an arrest will often engage in tasks just as hazardous. Teach disengagement as an option. Use every opportunity in scenario-based training to reinforce disengagement as a viable option. Will we ever eliminate all questionable police shootings? Barring some major technological breakthrough that might render obsolete the use of deadly force, it’s not likely. However, we can mobilize our existing resources to minimize the frequency of the problem, as well as strive to inform community leaders of the complexity of the problems we face in dealing with violent and potentially violent suspects. When all is said and done, there must be a universal understanding that suspect behavior is usually the precipitating factor in a police application of deadly force. That fact alone should be empowered to transcend class and ethnic distinctions. Send mail to webmaster@theppsc.org with questions or comments about this web site.

©2004 The Police Policy Studies Council. All rights reserved. A Steve Casey design.

|