Moving Targets Despite Department Rules, Officers

Often

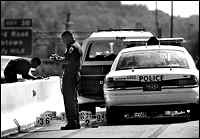

Second of five articles By Jeff Leen Hopping sidelong and holding his pistol in a two-handed grip, the man with the gun fired two shots through the side window of a Hyundai amid Monday morning rush-hour traffic on Florida Avenue. One horrified witness thought he was seeing a drug hit. But the shooter was D.C. police officer Vernell Tanner. His dead victim: an unarmed 16-year-old wanted for driving recklessly and running red lights. Tanner said the youth had tried to run him over. The death of Kedemah Dorsey on May 15, 1995, was not an isolated incident. A year earlier, Detective Roosevelt Askew had shot and killed unarmed 19-year-old Sutoria Moore as he sat in his car during a routine traffic stop. A year later, Officer Terrence Shepherd would shoot and kill unarmed 18-year-old Eric Anderson as he sat in his car during a routine traffic roadblock. In each case, the officer said he was forced to fire to prevent a "vehicular attack" by the driver. But the department eventually determined all three of the shootings to be unjustified. In the last six months, the District has agreed to pay $775,000 to settle lawsuits brought by survivors in the three cases. Like their counterparts in cities across the United States, D.C. police are instructed to shoot at unarmed people in cars only in extremely rare cases, to protect their lives or the lives of others. Yet since mid-1993, D.C. police officers have fired their weapons at cars 54 times in response to alleged vehicular attacks, killing nine people and wounding 19, an eight-month Washington Post investigation has found. In the overwhelming majority of those cases – and in all of the fatal shootings – the driver was unarmed. "That's really chilling," said James Fyfe, a criminologist at Temple University and former New York City police lieutenant who has researched police shooting patterns for two decades. "What's happening is the District is bearing the cost of the errors of the past, the way they've hired and trained these officers." Despite the discipline imposed on officers in some individual cases, the overall pattern of car shootings has continued throughout the 1990s. On Aug. 21, D.C. police surrounded a motorist on Interstate 295 who had vandalized one car and rammed three others, including two police cars, police said later. The trapped driver rammed a car carrying three passengers. To protect them, Officer Jacques Doby killed the unarmed driver by firing repeatedly into the truck. Doby shot 38 bullets, reloading twice, according to a police official. "I'm really concerned about all these shootings," said Terrance W. Gainer, the department's new executive assistant chief. "What we're seeing in these cases are officers inappropriately putting themselves in harm's way because we haven't trained them well." On Friday, Chief Charles F. Ramsey announced a new policy on the use of force placing even further restrictions on officers attempting to stop cars. "When confronted with an oncoming vehicle, [the] officer should move out of its path," the new policy states. Car Cases Conflict With

Standard Policy Police in Washington and throughout the country are restricted in shooting at cars for both common-sense and legal reasons. Bullets tend to ricochet off car bodies. And if an officer hits a criminal driving a car, the officer may only succeed in turning the vehicle into a 2,000-pound unguided missile. "To successfully fire at a vehicle, let alone a moving one, is something that only seems to work well in the movies," a training manual produced for the D.C. police warns. "In real life your odds of 'killing' a car are about as good as becoming the next chief of police." Finally, District law – reflecting common practice across the country – does not permit police to shoot even at fleeing felons in cars unless they pose an imminent threat to lives. The 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in 1996, for example, reinstated a $259,000 judgment against a San Francisco police officer who shot and killed the driver of a slow-moving car. The officer said he fired because the car was about to run him over. But the court found that "a reasonable officer could not have reasonably believed that shooting a slowly moving car was lawful," even though the driver was wanted for a purse snatching. "Our policy is you never fire at a vehicle," said Detective Walter Burnes, spokesman for the New York Police Department. "The contention here is if a vehicle is coming at you, you have the option to get out of the way." The number of car shootings by District police far exceeds the numbers for other high-crime cities like New York City and Miami, The Post found. "Most departments have moved to prohibit these kinds of shootings, unless somebody in the cars was armed and shooting at the officers," said Michael Cosgrove, a former Miami assistant chief who has testified as an expert in police shooting cases. None of the 54 Washington car shootings examined by The Post involved drivers or passengers shooting at officers, according to police and court records. In nine cases, the department ruled the shootings unjustified and disciplined officers, The Post found. Of the nine fatal car shootings, five were ruled unjustified, one was ruled justified and three are pending. Of the 29 car-shooting cases in which detailed information could be culled from police and court files, The Post found that 16 occurred after traffic stops and an additional 11 when police made felony arrests, three of them for alleged violent offenses. In five cases, the driver was found to be armed but did not shoot at police. In three cases, officers made statements that investigators considered false about the circumstances surrounding fatal car shootings. The Post examined 13 cases from the last five years in which a driver who was shot at by police was charged with assaulting an officer with his car. Only one of the 13 was convicted. Officials Fail to

Notice Rising Problem The parade of incidents has not generated much official reaction. Not at the department, which investigated all the incidents. Not at the corporation counsel's office, which has defended police in more than a dozen lawsuits related to car-shooting cases in the last three years. And not at the U.S. attorney's office, which reviews all fatal shootings involving D.C. police. "I do kind of remember more than a few in cars," said Deputy U.S. Attorney General Eric H. Holder Jr., who was the District's U.S. attorney when the cases were reviewed. "I don't know if that's typical of what you find in police shootings outside D.C." It isn't, according to experts and officials in other departments. From 1995 through 1997, for example, D.C. police officers fired at cars 29 times to defend against vehicular attacks, according to department documents. In the same period, New York City police, with more than tenfold the number of officers, fired at cars 11 times. Geoffrey Alpert, a criminologist at the University of South Carolina who reviewed a dozen summaries of car-shooting cases prepared by The Post, said he saw a pattern of D.C. officers approaching suspicious vehicles from the front on foot, making themselves vulnerable. "Clearly, officers are putting themselves in bad positions," said Alpert, who has advised large city police departments on the use of force. "They're putting themselves in harm's way as a justification for using deadly force." Lowell Duckett, a former D.C. police lieutenant who was a firearms instructor at the police academy, said training for firearms and "vehicle skills" – how to stop vehicles involved in felonies, when to shoot at cars – was cut back just as a record influx of new recruits arrived in 1989 and 1990. Officers from those classes were involved in more than half of the 54 car shootings examined by The Post. "We said then, 'You're going to have more police shootings and they're going to be unjustified,'‚" Duckett said of the training cutback. Other D.C. officers say that criminals in the District often use their cars to try to escape and that fast-moving circumstances may force officers to shoot. "The mind-set was to get away from the police," said Claude Beheler, a retired deputy chief. "You can't shoot at a fleeing vehicle. There are strict guidelines to never shoot at a moving vehicle unless the vehicle could cause serious bodily injury or death. But these things happen in split seconds. Things move quickly. These cases are difficult." Most departments don't track the number of times their officers shoot at people in cars. Alpert at the University of South Carolina collected data showing that the Miami-Dade Police Department in Florida had 49 car shootings from 1984 to 1994. Miami-Dade's 10-year total is less than the District's five-year total, even though Miami-Dade has twice the population, nearly as many officers and more crime. D.C. officers in five years killed nine people in cars, compared with four in 10 years for the Miami-Dade officers. The D.C. officers also fired three times as many bullets per car shooting – an average of six, to two for the Miami-Dade officers. The D.C. shootings differed in another way: Twelve of the D.C. car shootings occurred while the officers were off duty, compared with one for the Miami officers. Off-duty shootings generally are considered more problematic than on-duty shootings because citizens may be unaware they are dealing with police officers and because officers without adequate backup often feel more vulnerable. What follows is a look at five D.C. police car-shooting cases that left four people dead and one person wounded. The first case involved a conspiracy, and two officers were criminally indicted and convicted. The middle three shootings were declared unjustified by the police department, and one officer has been fired. The last shooting was ruled justified even though officers' accounts conflicted. In each case, according to witness statements and forensic evidence, the threat to the officer who fired appeared minimal. In the five incidents collectively, the sum total of jail time for the officers involved was 15 days.

At 1:41 a.m. on July 15, 1994, Detective Roosevelt Askew pulled up to help Sgt. William Middleton, who had stopped a 1993 Geo Prizm in the 3400 block of 15th Street SE. The Geo had run a stoplight and had tags that did not match the vehicle listed in the police computer. The driver "gunned the engine and took off at a high rate of speed, driving directly at an officer who was surrounding the vehicle," a police report said. Askew fired once "in an effort to stop the assault" on Middleton, the report said. The driver, Sutoria Moore, 19, was hit in the back of the neck. He was taken to D.C. General Hospital and pronounced dead at 3:29 a.m. The police report was a series of lies: Middleton had not been standing in front of the car. The unarmed driver had not tried to run him down. And Askew had not fired to protect Middleton. Prosecutors soon found themselves confronted by a coverup that used a "vehicular attack" story to conceal an unjustified shooting. Suspicions were raised because the officers' accounts conflicted with the physical evidence. Askew acknowledged to a prosecutor in early 1995 that his gun went off accidentally when he pushed himself away from the car body as Moore suddenly revved the engine. He later said his conscience had been bothering him. "I knew in my heart that the truth had to come out," Askew said in a civil deposition. Askew said Middleton suggested the vehicular attack story while they were sitting alone in Middleton's police cruiser minutes after the shooting. Askew said he was in shock at the time and "had the mind of a child. I believe Sergeant Middleton took advantage of that situation." Middleton, in his civil deposition, said it was Askew who concocted the story. Middleton said that Gregory Archer, the first homicide detective on the scene, questioned Askew in Middleton's patrol car while Middleton sat in the front seat, a violation of the department's requirement that officers involved in shootings be separated during the investigation. Archer said in an interview that he did not recall whether he placed the officers in the same car. As Archer interrogated him, Askew told the vehicle attack story and appealed for Middleton's support, saying, "Come on, Sarge, help me out," according to Middleton's account. Middleton also discounted Askew's subsequent version that the gun discharged unintentionally. "He had to have fired the gun on purpose," Middleton said. "But his reason for it, I don't know." Exactly three years after the fatal shooting, Askew pleaded guilty to lying about it. A Marine Corps veteran with 24 years on the D.C. force, Askew, 51, was sentenced to two years' probation and a $5,000 fine on the misdemeanor charge. Askew did not respond to messages seeking comment. Three days later, Middleton, 47, also pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor for saying that he had been in front of Moore's car during the shooting when he actually had been on the driver's side. He got a six-month sentence, with all but 15 days suspended. Like Askew, he is no longer on the force. Middleton said in an interview he had never worked with Askew before and had no reason to lie for him. "I felt like he thought he saved my life, so I kind of put myself in a position that I wasn't really in," Middleton said. "I was in for 27 years [on the police force]. I was out there making traffic stops, arresting people, writing tickets. I always felt that when I got my paycheck, I wanted to earn it," Middleton said. "You'd be surprised the heartache I had behind this death. It really hurt. It really, really hurt." The car Sutoria Moore was driving turned out to have been stolen in a carjacking three days before the shooting, but Askew and Middleton did not know that when they made the traffic stop. Moore had only one charge on his police record, a traffic citation for driving without a permit when he was 16. After Moore's death, his mother sued. The

District settled the case last summer by paying her $375,000.

'Here's Someone Getting Murdered' Shortly before 9 a.m. on May 15, 1995, Officer Vernell R. Tanner was outside Banneker Senior High School at 800 Euclid St. NW, where he was assigned as a beat officer. Tanner saw a white Hyundai heading the wrong way up a one-way street, doing about 50 in a 15-mph zone, he later said in a sworn deposition. Two girls told Tanner the car had almost hit them. Tanner, 47, a 26-year veteran of the force, drove after the Hyundai in his private car, a Toyota Camry. Because he was working on foot at the school, he was not required to have a patrol car. After unsuccessfully trying to stop the Hyundai without the benefit of a siren or a police light, Tanner radioed that he was pursuing a car that had nearly struck two pedestrians. He later said in a sworn deposition that he was told to break off the pursuit; D.C. police permit officers to chase suspects only when they believe a felony has been committed and the suspects are dangerous. Moreover, officers must be in a marked patrol car to participate in a chase. Despite the dispatcher's instructions, Tanner continued the pursuit. His intent, he said later, was to keep the car in sight until a marked police car arrived. He eventually pulled up behind the Hyundai, blocking it behind a line of rush-hour traffic on Florida Avenue. Climbing from his car, Tanner confronted the driver. Tanner said he pulled his gun when the Hyundai backed up and rammed his car. Lawyer Doug Sparks, sitting in traffic a few cars behind Tanner's and the Hyundai, said he saw Tanner standing next to the Hyundai driver's door talking to the driver. Tanner had his back to Sparks, who did not know he was a police officer. Sparks heard a shot as the Hyundai began to pull out of the line of traffic. A few seconds later, Tanner fired a second shot as he "sidestepped," hopping with his gun pointed into the car, to keep up with the Hyundai as it moved across the oncoming lane of traffic, Sparks said in an interview. "It was basically at point-blank range," Sparks added. "I thought, here's someone getting murdered in front of me. I thought it was some kind of drug shooting." The first shot hit the driver in the chest at close range, a police investigation later concluded. The second shot hit the driver in the back. He was pronounced dead shortly afterward. Tanner said later he fired the first shot because he feared that the Hyundai was about to run him over. "He turned the wheel to a hard left and then he accelerated, and I discharged my weapon," Tanner testified in a civil suit brought after the shooting. In a recent interview, Tanner said he did not remember firing the second shot that hit the driver in the back. "I was not conscious of the second shot, which is common in most police shootings," Tanner said. After the shooting, eyewitness Sparks said he saw Tanner pick his hand-held radio off the ground and heard him shout into it: "The guy tried to run me down!" Sparks told The Post: "That's not what I saw. That kid didn't have to die." The dead driver was Kedemah Dorsey, 16, a Bladensburg High School dropout who worked at a Roy Rogers restaurant. He was scheduled to be at work two hours after he was killed, his father said after the shooting. "I want someone to explain to me how an officer walks up to a car for a traffic violation – and a child gets killed," Dorsey's father, Joseph, told The Post at the time. "My reaction was out of fear – fear that he was either going to crush my leg or run me over," Tanner said in a recent interview. A lawyer hired by the Dorsey family disputed that. "It's somewhat difficult to use the car as a weapon when it is wedged in rush-hour traffic and the officer is standing to the side of it, not in front of it," said attorney Michael Morganstern, who sued the police on behalf of the Dorseys. The District settled the case for $150,000. The car technically was stolen, but Tanner did not know that. Dorsey had borrowed the car without permission from his older brother, a Marine stationed in Italy. Dorsey's mother had reported it stolen to "scare" the boy, according to his father. Tanner, a Marine veteran himself, was put on administrative leave with pay, pending an investigation. He had previously fired his weapon twice in his police career, he later testified. One of those shootings also involved a car and was ruled justified. After two years and seven months, the U.S. attorney's office decided not to bring charges against Tanner. "You can't prosecute the officer for putting himself in the wrong spot where he becomes vulnerable and then has to react," Ramsey Johnson, special counsel to the U.S. attorney, said of car-shooting cases in general. Training and supervision deficiencies, Johnson said, are not relevant to the making of a criminal case. But a department administrative investigation, not bound by the standards of a criminal prosecution, found the shooting unjustified. The District is now attempting to fire Tanner through police trial board hearings scheduled to resume Dec. 7. 'Fearing for My Life, I Fired' Two teenagers were speeding in a Plymouth to a liquor store called the 51 Club on Naylor Road SE, trying to beat the 2 a.m. closing time. They swerved to miss a braking car and hit a Potomac Electric Power Co. pole at 1:50 a.m. on Aug. 20, 1995. The driver, Damon Henry, an 18-year-old construction worker, flattened the left rear tire of the Plymouth with the impact. But he and Davon Williams, 17, drove on to the liquor store. They did not know it, but an off-duty police officer had witnessed the accident. Rodney Daniels, 29, was a three-year member of the force. Daniels lived in an apartment nearby and had taken his dog out for a late-night stroll. While Daniels checked the utility pole for damage, Henry and Williams got someone to buy them liquor and left the store within 10 minutes. Daniels heard the grinding of the Plymouth's tire rim coming down the road; a bystander, he later recounted, told him the hit-and-run car was returning. Daniels stepped into Naylor Road and raised his police badge above his head in one hand. In the other, he held his Glock 9mm, being careful not to point the gun at the oncoming car, he later told investigators. Daniels said he yelled "Police! Stop the vehicle!" three times. The car slowed when it was about 30 feet away and then sped toward him, Daniels said. "After the driver refused to stop and fearing for my life, I fired several rounds at the driver of the car," Daniels said in a written statement to investigators after the shooting. Daniels said the car was 20 feet away when he started to fire, and that he then "jumped" out of the way before firing more shots. The car missed Daniels, but Daniels – who fired 11 times – did not miss the car. Daniels's bullets hit the front and driver side of the Plymouth. Henry was hit in the back with a bullet that lodged in his spine, paralyzing his legs, according to a surgeon's report. Henry was charged with assaulting a police officer with a dangerous weapon – his car. His mother, Terri Henry, said at the time that passenger Davon Williams – who was not injured – said the two teenagers didn't realize Daniels was a police officer. Damon Henry, a ninth-grade dropout, had three previous felony arrests – two for assault with a deadly weapon – all of which had been dropped. His only conviction had been for misdemeanor destruction of property. Henry's injuries kept him from appearing in court, and the assault charge against him was dropped in January 1996. After months of rehabilitation, he was still unable to wash or dress himself and required close care for most of the day, according to court papers filed by his attorneys. Henry's injuries led to infections that caused septicemia, and he died on Feb. 5, 1997. Before he died, he sued the police. After his death, his mother took over the lawsuit, which is pending. Michael Cosgrove, a former Miami police assistant chief hired as an expert by the Henry family, said that Daniels used a "self-initiated threat" as a justification to fire. The District's expert, former D.C. police chief Jerry Wilson, said Daniels's actions were "consistent with the proper standards of care." On June 18, 1997, nearly two years after the shooting, the department's Use of Service Weapon Review Board concluded that the shooting was not justified. In a deposition in the civil suit, Daniels said his commanding officer had accused him of negligent use of a firearm. "He stated that I placed myself in that position," Daniels testified in the deposition. "As though I created the danger or the threat." Daniels received a nine-day suspension. He served four days of the suspension, and the rest were held in abeyance. He said in the deposition that he disagreed with the punishment "because I was in fear of my life. And also I was taking police action." Daniels said through a police spokesman that he could not comment because of pending litigation. 'I Pulled My Gun Out, It Went Off' Four 6th District officers were working overtime on a routine traffic roadblock on June 9, 1996, at 50th and C streets SE, checking whether drivers had valid licenses and were wearing seat belts. At 2:20 a.m., a blue 1985 Oldsmobile Cutlass Supreme pulled up. The driver, Eric Antonio Anderson, 18, of Landover, was alone in the car. Lt. Stewart Morris approached the Cutlass and asked the driver for his license and registration. Morris later told investigators he got "a bad feeling" and thought the driver was going to flee. Morris asked him to turn his engine off. "What do I got to do that for?" Morris said the driver responded. "I think we have got a problem," Morris shouted to the other officers at the roadblock. What happened next surprised Morris as much as it did Anderson, Morris said later. "I saw a flash coming from my left side and heard a single gunshot at the same time," Morris told investigators. "I looked to my left and saw Officer Terrence Shepherd." Shepherd, 22, who had been on the force two years, had come to back up Morris, but Morris said he was unaware of that until after the shot was fired. "I didn't hear Officer Shepherd say anything before, during or immediately after the shooting," Morris said. The bullet from Shepherd's gun passed through Anderson's left shoulder, aorta and esophagus before lodging in his right shoulder blade. Anderson's car went 50 feet in reverse and struck a tree. He was taken to Prince George's Hospital Center and pronounced dead at 2:55 a.m. He had a .04 percent alcohol level in his blood, well below the legal limit. No weapon was found in Anderson's car. Immediately after the shooting, Capt. Joshua Ederheimer, the commander of the roadblock, ran into Shepherd. "I said, 'Shep, what happened?'‚" Ederheimer later told police investigators. He said Shepherd responded, "Captain, I pulled my gun out, it went off, my finger was on the trigger." Ederheimer said he believed Shepherd was telling him the shooting was accidental. Shepherd was placed on administrative leave with pay pending a criminal investigation into the shooting. Shepherd told prosecutors he had switched places with Morris, stepping in front of him and questioning Anderson himself. This contradicted Morris's statement that he didn't see Shepherd until after the shot. Shepherd said he intentionally fired because he feared for his and Morris's safety. The driver refused commands to put his hands on the wheel, Shepherd added, and had rummaged in the car's console as if he was trying to get a weapon. Shepherd also said he heard the vehicle go into reverse and start to move. He said the car was now a threat to him and Morris and other officers on the scene. "Once he put the car in gear and went back, it was easy enough for him to put the car back in the driver's position and strike us," Shepherd later testified in a police disciplinary hearing. He said he fired after the car moved back three to four feet, according to an investigative report by police. But two other officers on the scene, James Minor and Jacques Doby, said in statements to investigators that the car did not start moving until after the shot. Both officers said they saw Shepherd slightly behind Morris after the shot – not in front of the lieutenant. The evidence also contradicted Shepherd: The gunpowder residue on Anderson's shirt indicated that he was shot from less than 24 inches away – not the three to four feet in Shepherd's account to investigators. The left-to-right path of the bullet through Anderson's torso also indicated he had been sitting still, not moving backward, when he was hit. Finally, a stain on the back left side of Morris's white uniform shirt turned out to be lead residue – "probably from gases emitted from the ejector on the right side of the weapon," according to a police laboratory report. That undermined Shepherd's story that he fired after moving in front of Morris. Eighteen months after the shooting, the U.S. attorney's office decided not to prosecute the case criminally. A spokesman for the office declined to comment. The police department started its own internal investigation and found that Shepherd's reasons for firing were "unsupported by witnesses or the evidence," Lt. Rodney Parks wrote. Parks said Shepherd should face administrative charges of using unnecessary force and making false statements. John C. Daniels, the 6th District commander, agreed with the force charge but disagreed with the false statement charge. After a disciplinary hearing before the department's trial board, Shepherd was fired on Oct. 23. At the hearings, Shepherd was portrayed as an officer with several commendations who had started his career in 1990 as a 17-year-old cadet in the police museum. Shepherd had had few complaints lodged against him; he had shot and killed a man who threatened him with a knife while he was off duty in 1994. He also had shot at a car in a previous incident. Both earlier shootings were ruled justified, according to his trial board testimony. Shepherd told The Post recently the police investigation was flawed. He disputed several of its findings and questioned the stain on the back of Morris's shirt, saying the shirt was not turned over to homicide until four days after the shooting. Shepherd said he plans to appeal his firing to an arbitration process. "There are other cases like this," he said. "The penalty they gave me I think was unjust. The only thing I did was assist another officer and it's like I'm the sacrificial lamb out of this ordeal." 'Unable to Escape ... the Car' At 8:01 p.m. on June 10, 1996, the 6th District vice unit interrupted an alleged drug deal in the 5500 block of B Street SE. The brief police report written that night said officers saw one man give another what appeared to be drugs; both men were arrested and taken to the 6th District station for processing. The report also noted that one of the men, while trying to escape, "aimed his vehicle in the direction of the police officers." Left out of the report was the fact that Lt. Elliott Gibson, the supervisor on the scene, shot the driver, James Theodore Willis, in the face. Willis was taken to D.C. General Hospital and later recovered. Willis, a 38-year-old department store receiving clerk who had a history of petty drug crimes, was charged with possession of cocaine with intent to distribute and assault on a police officer – for allegedly using his 1990 Buick in a vehicular attack. Officer Anthony McGee signed the police report. Gibson signed as the supervisor. McGee gave prosecutors a more detailed sworn statement on June 11, 1996, the day after the shooting, so they could formally charge Willis. McGee noted that 12 crack rocks were found in the car and six more in Willis's hand. Of the shooting, McGee simply wrote: "While Willis was driving on the sidewalk towards a group of children, a police officer shot Willis." The next day, McGee altered that account in a written statement to investigators probing the shooting. This time, he made no mention of children. His statement indicated that he didn't even see the shooting. "I then heard one gun shot and looked back and observed that Gibson had his weapon out," McGee said. Investigators never asked McGee to resolve the conflict between his two versions of the shooting, according to the department's final investigative report on the incident. McGee's second statement may have differed with his earlier sworn statement, but it did not contradict Gibson's: He told investigators he fired because the car was coming toward him and he was trapped on the sidewalk by a four-foot wall. "Unable to escape the path of the moving car, Lt. Gibson fired one round from his service [weapon] through the front windshield of the car," police documents filed in Superior Court note. But another officer on the scene, Carol Queen, contradicted Gibson. She said in a statement to investigators that the car was not moving when Gibson fired. Queen also said two officers were standing atop the four-foot wall that Gibson said had trapped him. In addition to McGee, three other officers at the scene told investigators they had heard but had not seen the shot. Among the five officers who said they had seen the shooting, three said the car had started to move forward, one said it had moved "slightly forward" and one said it came "directly at Lt. Gibson." Gibson said in his written statement to investigators that he fired from six feet away and that the car stopped six feet from him, an indication that the car had little forward momentum. Gibson was ruled justified by police investigators and later was promoted to captain. Gibson and McGee did not respond to messages seeking comment. Willis sued the District for assault and negligence, claiming he was shot while "sitting in his stationary vehicle." On Dec. 8, 1997, Willis appeared in court before Judge Mildred Edwards on the criminal charge. Willis's criminal defense attorney, Mark Rochon, said the police story changed "180 degrees" – dropping the original justification of shooting to protect children – because that version would have gotten Gibson in trouble with internal investigators for endangering the children with his gunfire. Rochon said that if Gibson had "fired his gun and there were kids behind the car, he wouldn't be keeping his job, he wouldn't be a captain now. He would be a sergeant." The next day, after negotiations with the government, Willis struck a plea bargain. In exchange for his guilty plea to lesser charges of cocaine possession and assault on a police officer – without the dangerous weapon component – Willis was sentenced to unsupervised probation. He walked out of court a free man. The next day, Willis dropped his civil suit against the department. Staff writers David Jackson and Sari Horwitz, database specialist Jo Craven, researcher Alice Crites and Metro Research Director Margot Williams contributed to this report. Send mail to webmaster@theppsc.org with questions or comments about this web site.

©2004 The Police Policy Studies Council. All rights reserved. A Steve Casey design.

|